|

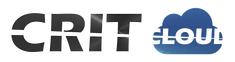

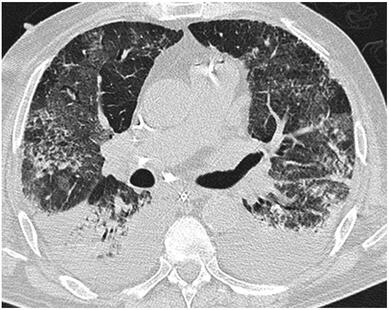

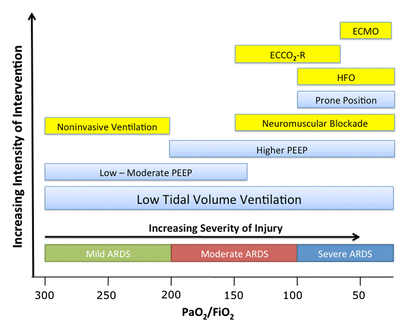

The lastest updated surviving sepsis guidelines for COVID-19 patient recommends a high-peep strategy in the intubated, mechanically ventilated patient. As most of these patients present with moderate to severe ARDS, PEEP is used to keep lung areas open and therefor to improve oxygenation. This seems to be especially true in the classical case of ARDS, where the lung become 'wet' and 'heavy' which results in widespread atelectasis of the dependent parts of the lungs, often further complicated by pleural effusions. Classical CT appearance in the acute phase of ARDS is an opacification with an antero-posterior density gradient. Dense consolidation in the most dependent regions merges into a background of widespread ground-glass attenuation and the normal or hyperexpanded lung in the non-dependent areas (Howling SJ et al. Clin Radiol 1998;53(2):105-109). The theory behind these changes is that the increased weight of overlying lung causes compression-atelectasis posteriorly. The fact that prone positioning these patients quickly redistributes these gradients supports this theory (Desai SR et al. Anaesthesiology 1991;74(1):15-23). Chest CT's in patients with COVID-19 often show ground-glass opacification with or without consolidations. These are changes often seen in viral pneumonia. Several case series suggest, that CT abnormalities seem to be mostly bilateral and tend to have a peripheral distribution, often involving the lower lobes. In contrast to the classical ARDS pleural thickening, pleural effusion and lymphadenopathy seem to be a less common finding (Shi H et al. Lancet Infect Dis 2020). The leading problem in COVID-19 patients with ARDS is hypoxemia, while hypercapnia does not seem to be a significant problem. Sometimes profound hypoxemia does not seem to correlate with patient symptoms at all. In regards to the images above, atelectasis might not be the predominant reason for V/Q mismatches in these patients. Observations of mechanically ventilated patients in our unit and other hospitals in Switzerland have shown, that higher PEEP levels (15cmH2O and higher) often result in significantly reduced compliance values complicating ventilation and favouring the development of pulmonary over-inflation. This observation might support the theory that patients with COVID do not represent the traditional manner of ARDS with distinctive atelectasis. Another observation that supports this theory is that COVID-19 patients often do not respond as clearly to Prone Positioning as classical ARDS patients do. More probably, V/Q mismatch seems so happen on a more microscopical level in COVID-Patients. Lung compliance is often normal on these patients and, therefore, applying high PEEP-levels does NOT add any benefit at all. Maybe the principle of less is more also applies to COVID-19 patients we treat (Gattinoni L et al. Intensive Care Medicine; 46, pages780–782(2020)) Looking at the New Surviving Sepsis Campain COVID-19 Guidelines: Given these considerations, the strategy with High PEEP-levels in general should be questioned in principle. The Aerosol-Danger of SARS-Cov-2The outbreak of the SARS Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) in China 2019 has within a short time spread around the globe and is just about to hit central Europe. Although about 80% of all confirmed cases develop a mild febrile illness, around 17% develop severe Corona viral disease (COVID-19) with findings of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), of which about 4% will require mechanical ventilation. Since this virus, which was previously unknown to humans, spread rapidly around the globe, a large number of patients requiring intensive medical care now arise within a very short time. The lungs are the organs most affected by COVID-19 because the virus accesses host cells via the enzyme ACE2, which is most abundant in type II alveolar cells of the lungs. This results in mainly type 1 respiratory failure, which often requires urgent tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. Due to viral shedding in the patient's lungs, COVID-19 spread mainly via droplets. Events like coughing, high flow nasal oxygen (High-Flow), intubation and more can cause aerosol generation, allowing these airborne particles to travel even further distances. Performing endotracheal intubation in these patients is, therefore, a high-risk procedure, and it is required to adhere to certain principles to avoid infection of health care providers. The Safe Airway Societies of Australia and New Zealand have published a consensus statement that describes the problem very well and provides practical tips based on the currently available evidence. 1. Non Invasive Ventilation (NIV) and High Flow Nasal Oxygen (High-Flow)Current evidence suggests that the failure rate of NIV in COVID-19 patients seems to be similarly high as observed among Influenza A patients. Failure in these patients resulted in higher mortality. In general, NIV is recommended to be avoided or at least used very cautiously! The utility of High-Flow in viral pandemics in unknown. There is some evidence suggesting a decreased need for tracheal intubation compared to conventional oxygen therapy. High Flow Nasal Oxygen is worth a try, although it has to be assumed, that this is aerosol-generating. High-Flow should only be used in (negative pressure) airborne isolation rooms, and staff should wear full personal protective equipment (PPE) including N95/P2 masks. NIV and High-Flow are NOT recommended for patients with severe respiratory failure or when it seems clear that invasive ventilation is inevitable!

|

Search

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed