|

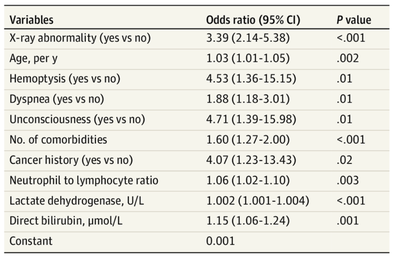

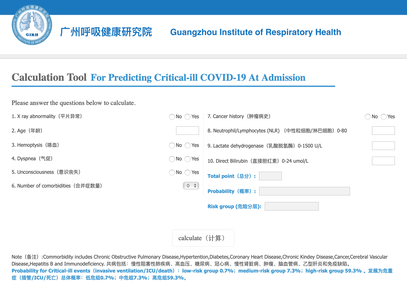

The treatment and management options of COVID-19 patient are rapidly evolving. The amount of research published daily is endless so that keeping an overview seems almost impossible. This short review of current publications is intended to overview current treatment options and its evidence. We will look at: - How do you Identify and Triage Patients at Risk for Severe Disease? - What about High Flow Nasal Cannulas (HFNC) and Non-Invasive Ventilation (NIV)? - Should we Prone Position the Spontaneously Breathing Patient? - When to Use Corticosteroids? - Should we Use Remdesivir? - What about Convalescent Plasma? - How do we Manage Thromboprophylaxis? How do you Identify and Triage Patients at Risk for Severe Disease? In an ideal world, we would be able to assess newly admitted patients with COVID-19 to predict the risk of getting critically ill in the course of the disease. Apart from a proper clinical assessment, JAMA published the COVID-GRAM Risk Score to address this problem. They used a cohort of 1590 patients to develop this score and validated this with a cohort of 710 patients. From 72 potential predictors, ten variables were independent predictive factors and were included in the risk score. The practicability in a clinical setting is not clear yet, and as any predictive score, there are several limitations when it comes to assessing a single patient instead of a cohort. The COVID-GRAM Score Calculator can be accessed via the following link: http://118.126.104.170/ Early identification of COVID-19 patients at risk for severe disease would be helpful for management. Every clinic/ ICU should have a triage and risk assessment tool at hand.

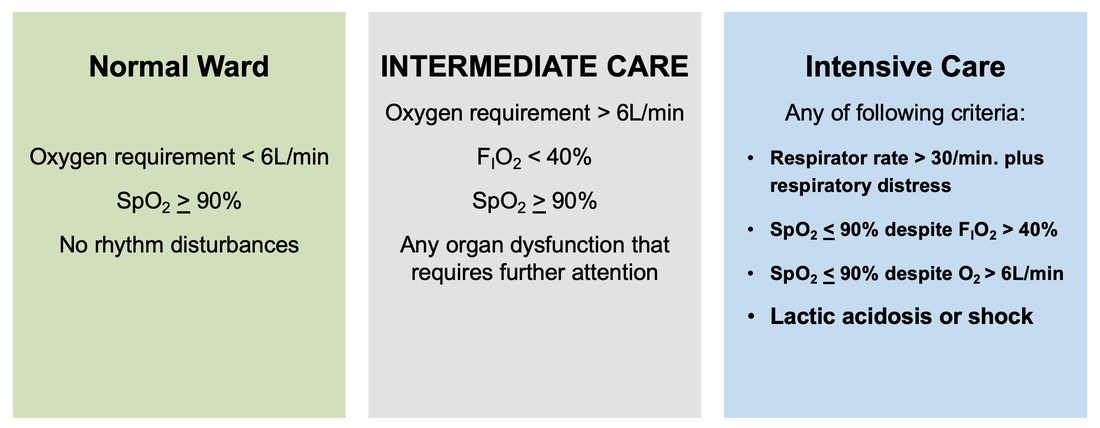

For triage, we use the following simple criteria: As a predictive assessment tool for severe disease the COVID-GRAM Calculator can be used:

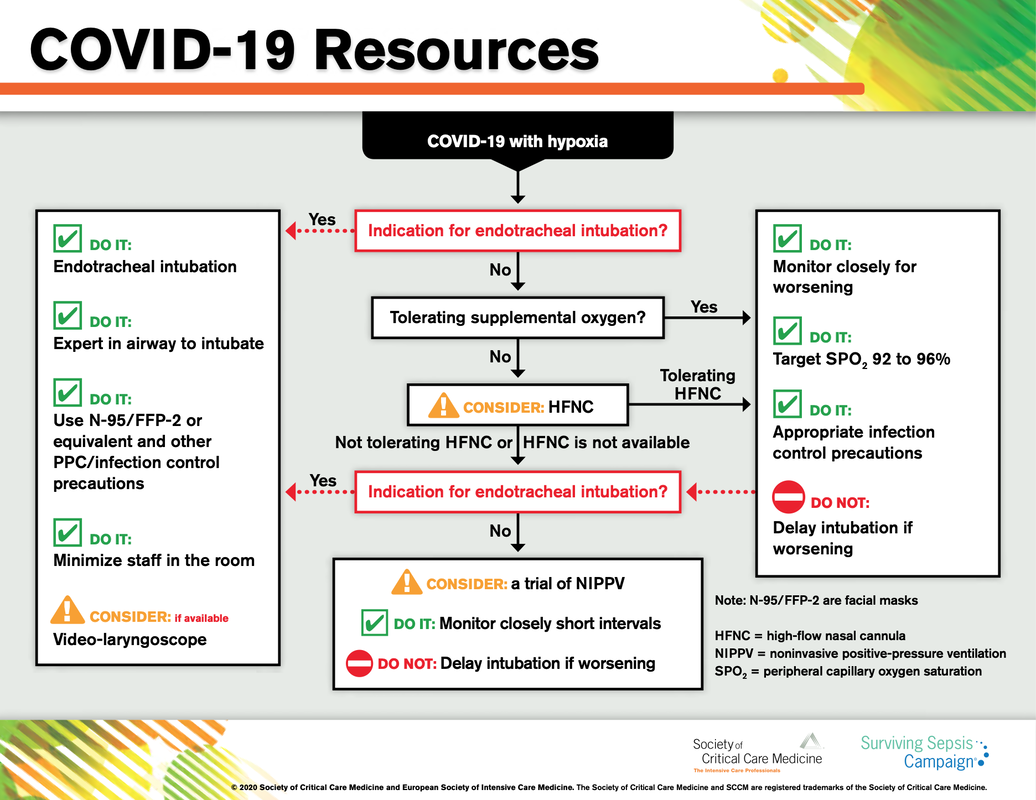

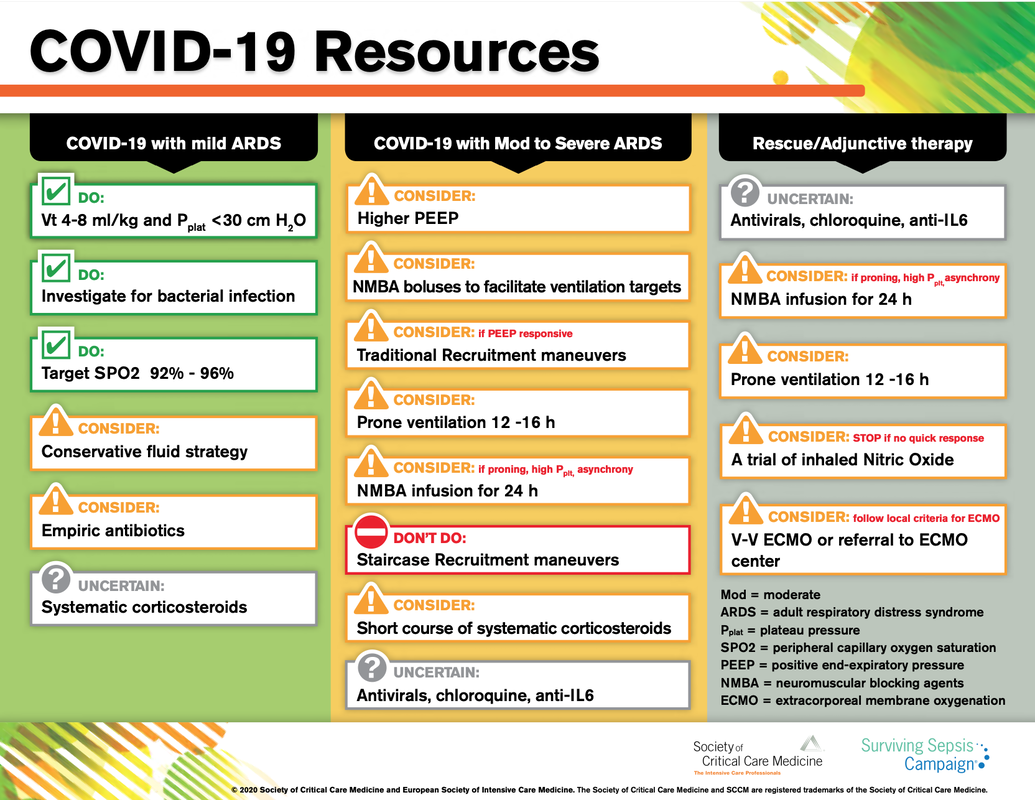

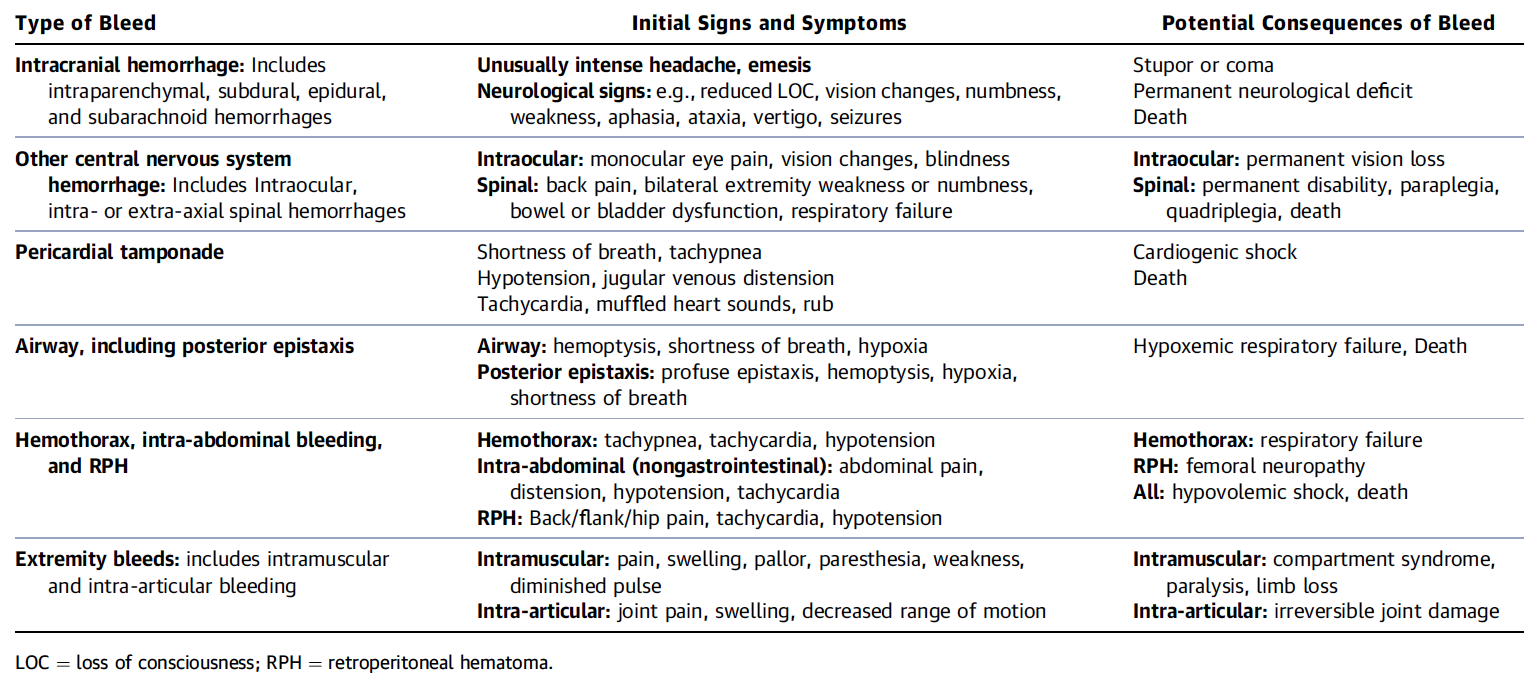

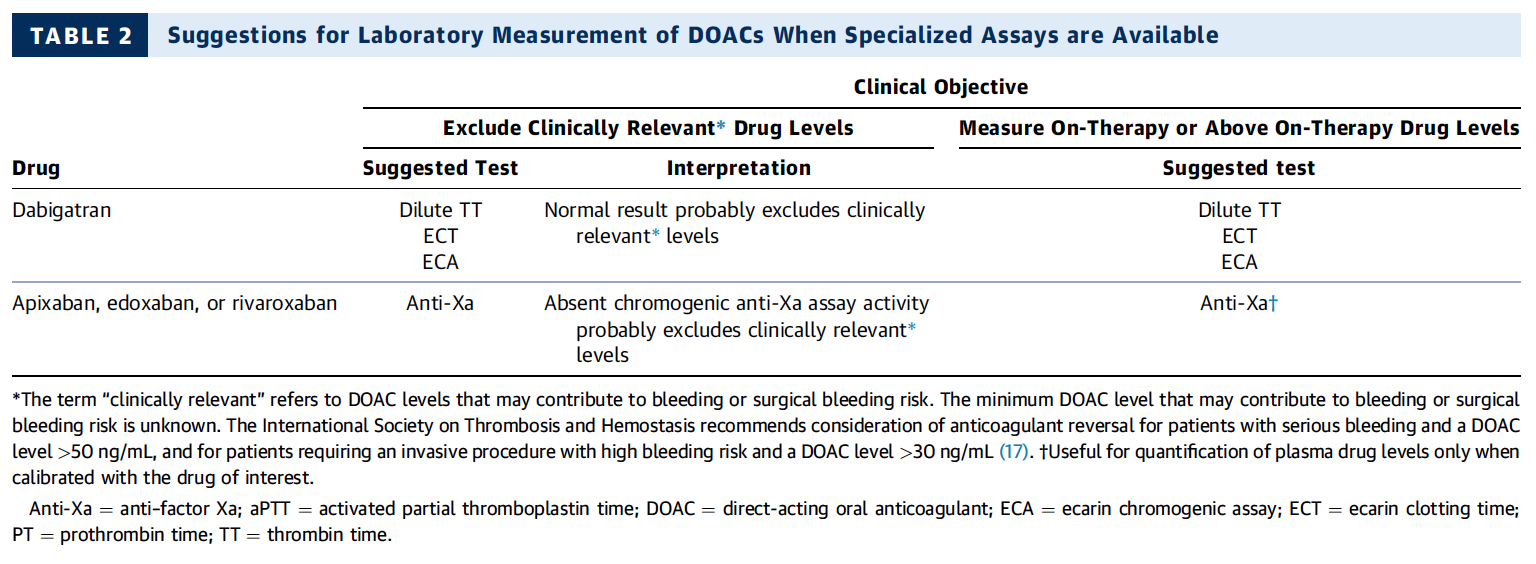

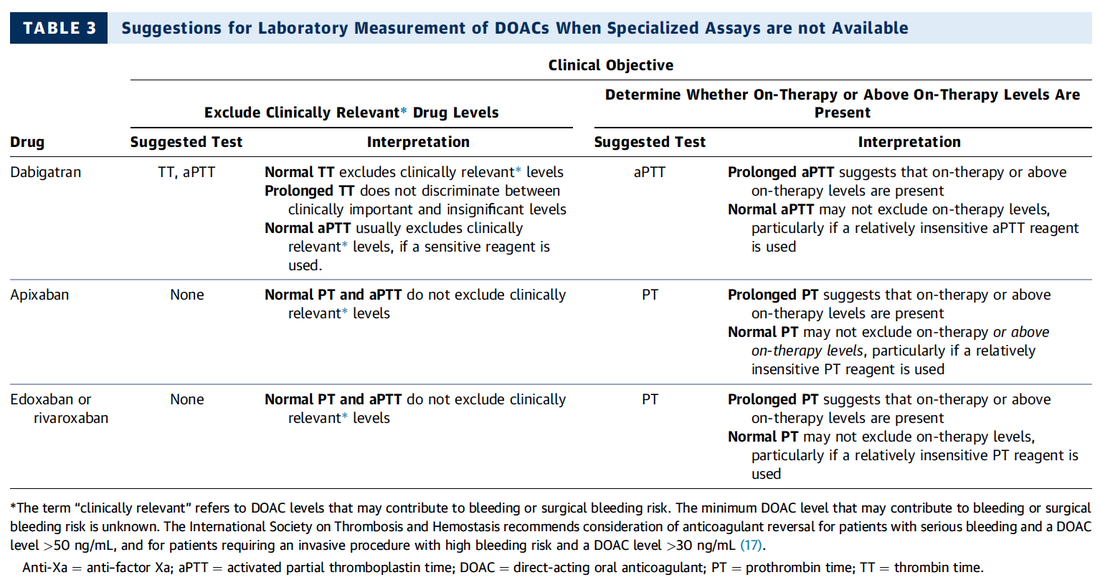

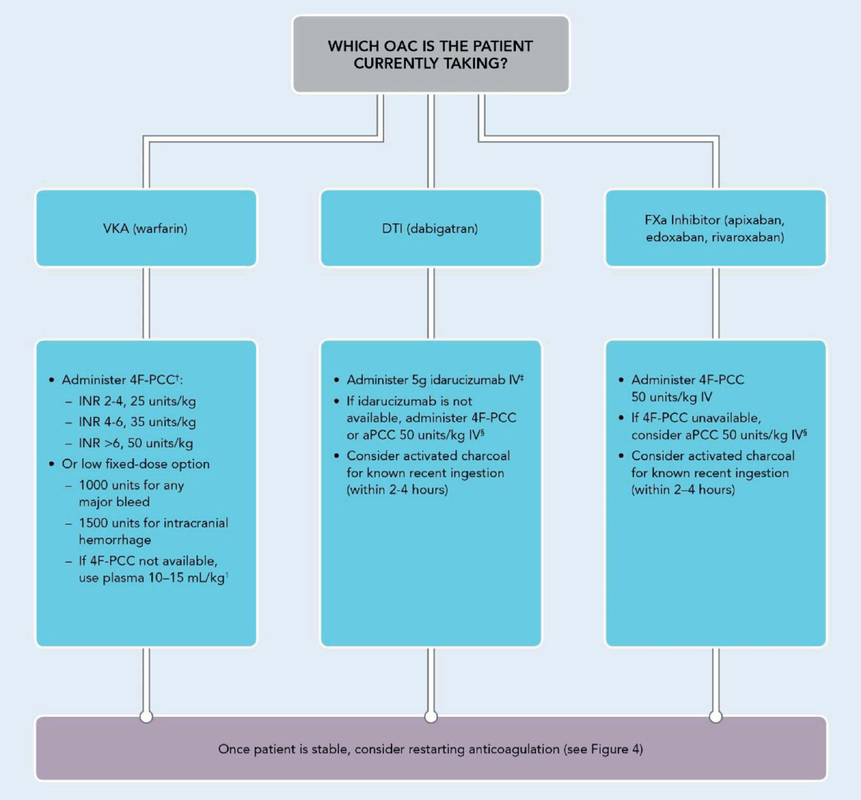

What about High Flow Nasal Cannulas (HFNC) and Non-Invasive Ventilation (NIV)? Especially at the beginning during the first wave of the pandemic, the use of HFNC and NIV was often avoided due to aerosolisation fear. Many ICU's tended to intubate their patients with respiratory failure relatively early. The lack of ventilators in some areas and reports that invasive ventilation is associated with high mortality (Zhou F, Lancet 2020; 395:1054) led to a constant change in management. KEEP IN MIND: Randomised-controlled studies for the treatment of COVID-19 patients with HFNC and NIV lack until now! Aerosolisation remains a big concern for health care workers (Niedermann MS; Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 201:1019, Wu Z; JAMA 2020, February 24) and the amount of leakage flows is highly variable (Winck JC; Pulmonology 2020, April 20). Experience during the year 2020 showed, that most critical care providers have moved to use NIV and HFNC more frequently than initially. Proper personal protection equipment is essential and minimises risk for health care providers. Some evidence supports this approach (Avdeev SN, Am J Em Med AJEM Volume 39, p 154-157). NIV and HFNC is feasible in patients with COVID-19 and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, even outside the ICU Helmet-NIV, leakage-free masks (non-vented masks) and double hose systems with virus-proof filters seem to be advantageous in this respect (Pfeiffer M; Pneumologie 2020, April 22). It is recommended that patients under HFNC should wear a surgical face mask over their cannulas Helmet NIV might advantageous compared to Mask NIV, though evidence is limited. (Patel BK et al. JAMA 2016. PMID: 27179847, single center study, trial stopped early, larger randomized-controlled studies awaited). KEEP IN MIND: Generally, there is only minimal evidence regarding the therapeutic benefit of these measures compared to their risks for the environment due to aerosolisation. Whether HFNC and NIV itself might produce self-inflicted lung injury (SILI) to some extend is not fully understood! Following patients should be considered for intubation and invasive ventilation - Severe hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2 <150mmHg or respiratory rate >30/min) - Persistent or worsening respiratory failure (i.e. O2 sat <88%, RR > 36/min) - Neurologic deterioration - Intolerance of face mask or helmet - Airway bleeding - Copious respiratory secretions Should we Prone Position the Spontaneously Breathing Patient?Since the publication of Guerin C et al. (N Engl J Med 2013; 368:2159) prone positioning of patients with moderate to severe ARDS has become standard procedure in ICU's around the world. It is, therefore, evident that this treatment modality seems appropriate for COVID-19-induced lung injury, too. Trying to avoid intubations, clinicians rose the question, whether a prone position in the spontaneous breathing patient could avoid the need for invasive ventilation or even improve outcome. Ding L et al. (Crit Care 2020; 24:289) published a small multicenter study including 20 patients, whereas in 11 patients intubation could be avoided by prone positioning patients under NIV or HFNC. Telias et al. published an JAMA editorial (JAMA. 2020;323(22):2265-2267). He states that the prone position can improve oxygenation and can potentially result in less injurious ventilation. Unfortunately, this does not necessarily equate to lung protection and a better outcome. While improved oxygenation might prevent clinicians from intubating a patient, delayed intubation might worsen the patient's outcome. Regarding some evidence showing improved oxygenation during prone position, there are reasons to give it a try (Caputo ND et al. Acad Emerg Med Published online April 22, 2020). In the hypoxemic patient with no relevant respiratory distress awake prone positioning is a valid option - Use nasal cannulas or HFNC first - If comfortable enough, ask the patient to self-prone - Encourage the patient to remain in the prone position as long as well tolerated - Patients need close nursing and appropriate monitoring - Select prone positioning mattresses might be of help When to Use CorticosteroidsPatients with COVID-19 often show a biphasic course of the disease. The first phase is characterised by profound virus replication which decreases significantly after 5-7 days. After 7-10 days, a second phase develops in which an excessive or dysfunctional immune response can appear. This can lead to ARDS and multi-organ failure, which might be tackled by immunomodulating therapy. The largest, pragmatic randomised control trial we have at this stage is RECOVERY, performed in 176 hospitals around the UK and including more than 6400 patients (RECOVERY Collaborative group, N Engl J Med, July 17, 2020). COVID-19 patients that required oxygen or mechanical ventilation and presented with symptoms for at least seven days showed a significant reduction in 28-day mortality when treated with 6 mg Dexamethason OD for up to 10 days. Patients in the early viremic phase or patients that not required any oxygen performed worse with Dexamethasone. A broader insight into this topic brings a meta-analysis from JAMA in September 2020, including seven studies: DEXA-COVID19, CoDEX, RECOVERY, CAPE COVID, COVID STEROID, REMAP-CAP and Steroids-SARI. They ended up looking at 1703 patients and found a significant reduction in 28-day mortality when treated with steroids compared to placebo. Patients with COVID 19 that require oxygen, HFNC, NIV, mechanical ventilation or ECMO should be treated with steroids In patients not requiring oxygen, there is a trend towards harm when giving steroids - In these situations, steroids are NOT indicated Should we Use Remdesivir?Brief: Evidence in regards to the treatment with remdesivir is scattered and inconclusive. In the largest randomised control triad available so far is ACTT-1 looking at about 1600 patients (Beigel JH et al. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:1813-1826). In a few words, remdesivir showed a trend towards a 4-5 day shorter time to recovery, but not if symptoms existed for more than nine days. There was no significant influence on mortality, except maybe for patients requiring oxygen but not any help in ventilation. If at all, remdesivir might provide some advantage in a very selected patient group, but even this remains debatable. For this reason, many consider remdesivir the 'Tamiflu for COVID-19'. Two other papers remain to be mentioned briefly: Wang et al. (The Lancet; April 29) presented results from a relatively small study which was terminated early and showed no statistically significant clinical benefits of remdesivir - except for a trend towards a shorter duration of illness. Goldmann JD et al. presented the so-called '5 versus 10 days study', a phase 3 multicentre study with 397 patients. The primary outcome was their clinical status on day 14, secondary outcome patients with adverse events. Interestingly a 5-day course of remdesivir resulted in a better clinical outcome that a 10-day course. Again, It did not show any benefit compared to placebo. Remdesivir - The "Tamiflu for COVID-19" There is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of Remdesivir strongly. It is expensive, and if used, maybe there is only a short time window reasonable to act. Should We Use ECMO?During the early phase of the pandemic, first reports raised some concern that ECMO in COVID-19 patients might be associated with very high mortality (Henry BM et al. J Crit Care; 58:27). In the meanwhile, though we have new results from a more extensive cohort study looking at data from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organisation (ELSO, Barbaro RP et al. Lancet Volume 396, ISSUE 10257) The investigators looked at 1035 COVID-19 patients from 36 countries that were treated with ECMO (mean age 49 years, 74% male). 70% of all patients had relevant co-morbidities. The median time of ECMO support was 14 days. The incidence of in-hospital mortality 90 days after the initiation of ECMO was 37·4%. Mortality was 39% in patients with a final disposition of death or hospital discharge. These results are comparable with earlier mult-centre studies with patients suffering from non-COVID-19 ARDS (Combes A et al. N Engl J Med 2018; 378:1965). A retrospective cohort study from France looking at 83 patients treated with ECMO showed a probability to die after 60 days of 31%. Mortality at the time of the last follow-up was 36% (Schmidt et al. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8:1121-1131). Various Societies recommend the use of ECMO in COVID-19 patients with treatment-refractory lung failure (Surviving Sepsis Campaign, ESICM, SCCCM and ELSO, WHO) Regarding the ongoing pandemic and limited resources, uniform indication and selection criteria for ECMO use should be available What about Convalescent Plasma?After a negative small randomised control trial (Li L et al. JAMA. 2020;324(5):460-470), a controversial Emergency Use Authorisation was granted by the FDA on 23.8.20 due to an observational study with a favourable effect on mortality with a high specific IgG content and onset less than days after symptom onset (Joyner MJ et al. MedRxiv; https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.12.20169359 - non peer-reviewed). At this stage the use of covalescent plasma can not be recommended How do we Manage Thromboprophylaxis?COVID 19 undoubtedly causes an inflammatory state that seems to trigger thrombotic activation in the venous and the arterial circulation. Thromboembolic complications are common, but the evidence is not robust on whether prophylactic or therapeutic doses should be used. Patients often have a significant elevation of D-dimers, an acute phase reactant representing the severity of disease rather than the dosage of thromboprophylaxis. One observational study looking at 1716 patients found no improved outcomes among in-hospital patients with COVID-19 when treated with therapeutic anticoagulation compared to prophylactic dosing. Moreover, patients who were started on anticoagulation for COVID-19 without evidence of thrombosis, new VTE, or new atrial fibrillation had worse outcomes compared to patients who were on prophylactic anticoagulation (Patel NG et al. Thrombosis Update; Volume 2, 2021, 100027) A case-based review of current literature and the COVID-19 specific coagulopathy end with the same finding that all in-hospital patients should receive prophylactic thromboprophylaxis. Whether a higher dose of prophylactic anticoagulation may be more effective is currently unknown (Chen EC et al. Oncologist. 2020 Oct; 25(10): e1500–e1508.). A small and retrospective study with 152 patients showed a lower risk of death and a lower cumulative incidence of thromboembolic events in patients with respiratory failure when a high-dose thromboprophylaxis was used. (Jonmarker S et al. Critical Care volume 24, Article number: 653 (2020)). Evidence supports the use of prophylactic thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19 Whether a higher dose of anticoagulation might be more effective is currently unknown Mind the GAPS Study - Compression Stockings are Useless for Most Elective Surgery Patients!14/9/2020

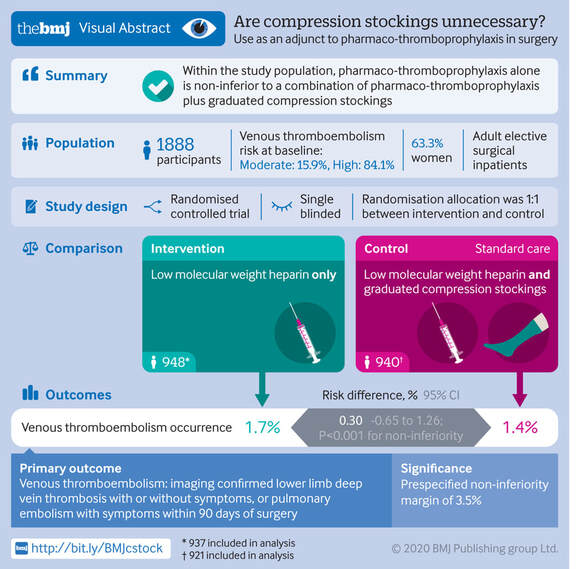

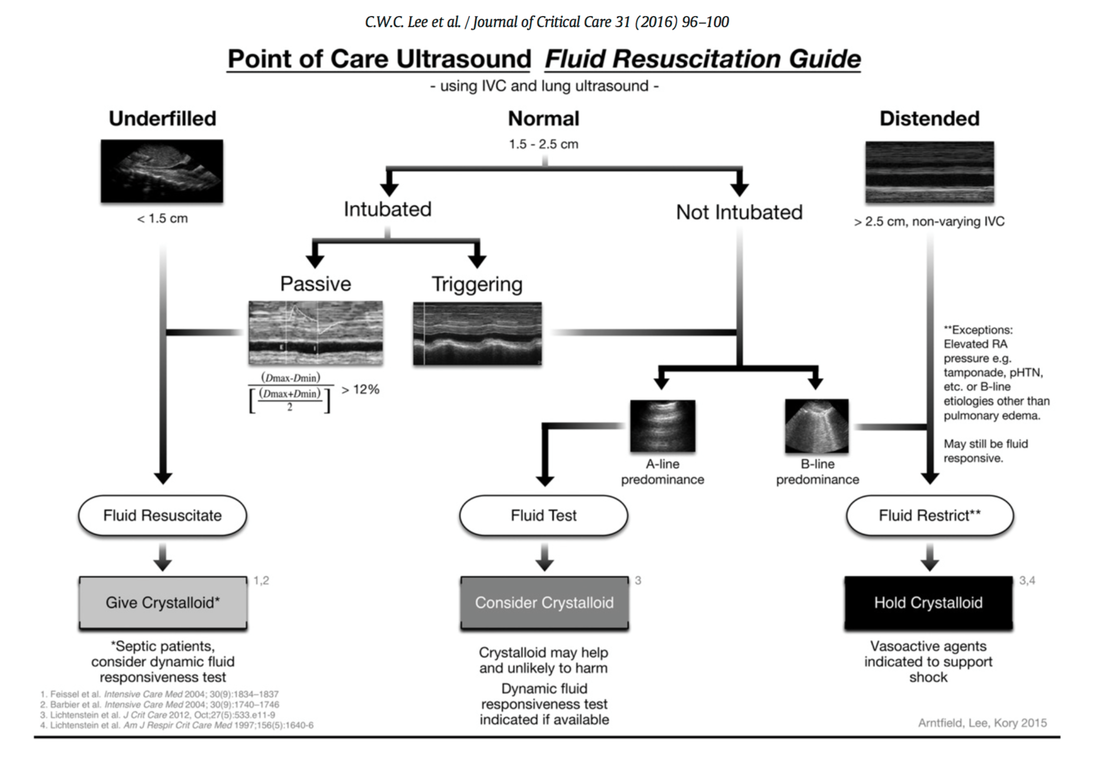

Cricoid pressure prevents aspirations, preoperative antibiotics avoid infections, and compression stockings protect against deep vein thrombosis. Many medical measures aim to reduce morbidity and mortality among patients, but unfortunately, the benefit of these measures is often not, or insufficiently, proven. Under certain circumstances, they may lead to additional problems or even cause harm (e.g. cricoid pressure Read Here). Time has definitely come to take a closer look at compression stockings for surgical patients. Apart from the fact that they look terrible, they are just as uncomfortable to wear and even carry certain risks in patients with peripheral vascular disease, for example. The effectiveness of compression stockings in modern practice has been questioned, but robust evidence has been lacking. This seems to change, as the long-awaited GAPS-Trial has been published and now provides further evidence on what concern patients undergoing elective surgery. Among this population, adding compression stockings to pharmaco-thromboprophylaxis was non-superior compared to pharmaco-thromboprophylaxis alone (primary outcome). There was also no difference in the quality of life outcomes found (secondary outcome). There is now some robust evidence to omit compression stockings in surgical patients that receive pharmacological thromboprophylaxis. Shalhou J. et al. BMJ 2020;369:m1309 The European Society of Intensive Care Medicine ESICM and the Society of Critical Care Medicine SCCM have been very efficient in providing us health care workers with a guideline manuscript giving recommendations on the treatment of COVID-19 patients in a critical care setting. It is imperative to keep in mind that research is moving forward very quickly in these times and changes to these recommendations are likely to occur. A collection of many reliable OPEN ACCESS platforms on SARS-CoV-2 can be found on www.foam.education. Infection ControlWhen performing aerosol-generating procedures on patients with COVID-19 in the ICU, fitted respirator masks (N95 respirators, FFP2) should be used (in combination with full Personal Protective Equipement PPE) Aerosol-generating procedures on ICU patients with COVID-19 should be performed in a negative pressure room During usual care for non-ventilated and non-aerosol-generating procedures on mechanically ventilated (closed circuit) patients surgical masks are adequate For endotracheal intubation video-guided laryngoscopy should be used, if available In intubated and mechanically ventilated patients, endotracheal aspirates should be used for diagnostic testing Supportive CareIn COVID-19 patients with shock, dynamic parameters like skin temperature, capillary refilling time, and/or serum lactate measurement should be used in order to assess fluid responsiveness For the acute resuscitation of adults with COVID-19, a conservative over a liberal fluid strategy is recommended For the acute resuscitation of adults cristalloids should be used - avoid colloids! Buffered/balanced crystalloids should be used over unbalanced crystalloids Do NOT use hydroxyethyl starches! Do NOT use gelatins! Do NOT use dextrans! Avoid the routine use of albumin for initial resuscitation! In shock use norepinephrine/ noradrenaline as the first-line vasoactive agent The use of dopamine is NOT recommended Add vasopressin, if target MAP cannot be reached Titrate vasoactive agents to target a MAP of 60-65 mmHg, rather than higher MAP targets For patients in shock and with evidence of cardiac dysfunction and persistent hypoperfusion despite fluid resuscitation and norepinephrine, adding dobutamine should be used For persistent shock despite all these measures, low-dose corticosteroids should be tried Ventilatory SupportKeep peripheral saturation SpO2 above 90% with supplemental oxygen

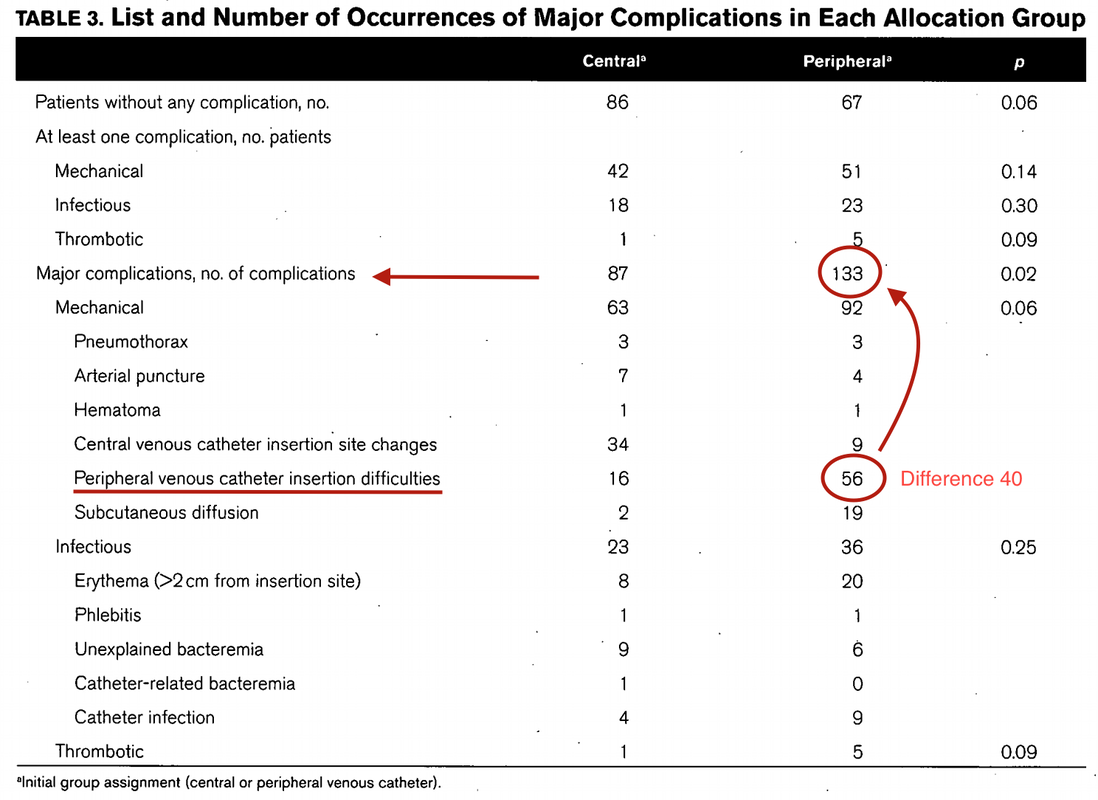

There is NO need for supplemental oxygen with SpO2 above 96% In acute hypoxemic respiratory failure despite conventional oxygen therapy, high-flow nasal cannulas (HFNC or High-Flow) should be used next High-Flow should be used over non-invasive ventilation (NIV) If High-Flow is not available and there is no urgent need for endotracheal intubation, NIV with close monitoring can be tried In the event of worsening respiratory status, early endotracheal intubation should be performed In mechanically ventilated patients, low-tidal volume ventilation should be used: 4 to 8 ml/kg In mechanically ventilated patients with ARDS targeting plateau pressures (Pplat) of < 30 cm H2O should be aimed for In patients with moderate to severe ARDS, a high-PEEP strategy should be used (PEEP >10cmH2O). Patients have to be monitored for potential barotrauma NOTE by Crit.Cloud: The strategy for high PEEP levels in general is currently discussed controversially. Observations in our own unit showed, that high PEEP levels tend to impaire compliance and therefor the quality of ventilation. Read also: "Less is More" in mechanical ventilatio, Gattinoni L. et al. Intensive Care Med (2020) 46:780-782 Patients with ARDS should receive a conservative/restrictive fluid strategy In moderate to severe ARDS, prone positioning for 12-16 hours is recommended To facilitate lung protective ventilation in moderate to severe ARDS, intermittent boluses of neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBA) should be used first In the event of persistent ventilator dyssynchrony, the need for ongoing deep sedation, prone ventilation, or persistently high plateau pressures, a continuous NMBA infusion for up to 48 hours should be used next Do NOT use inhaled nitric oxide in COVID-19 patients with ARDS routinely In severe ARDS and hypoxemia despite optimising ventilation and other rescue strategies, a trial of inhaled pulmonary vasodilator as a rescue therapy can be considered; if no rapid improvement in oxygenation is observed, the treatment should be tapered off If hypoxemia persists despite optimising ventilation, recruitment manoeuvres should be applied If recruitment manoeuvres are used, DO NOT use staircase (incremental PEEP) recruitment manoeuvres If all these measures fail, the patient should be considered for venovenous ECMO COVID-19 TherapyIn mechanically ventilated patients WITHOUT ARDS, systemic corticosteroids should NOT be used routinely In contrast, mechanically ventilated patients WITH ARDS, the use of systemic corticosteroids is recommended Mechanically ventilated patients with respiratory failure should be treated with empiric antimicrobials/antibacterial agents Critically ill patients with fever should be treated with paracetamol (acetominophen) for temperature control In critically ill patients standard intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) should NOT be used routinely Also, the routine use of convalescent plasma is NOT recommended The routine use of lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra®) is NOT recommended Currently, there is insufficient evidence to issue a recommendation on the use of other antiviral agents in critically ill adults with COVID-19 Currently, there is insufficient evidence to issue a recommendation on the use of recombinant interferons (rIFNs); chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine; tocilizumab (humanised immunoglobulin) Teaching in medical school and opinions in literature are in agreement: The application of vasopressors requires central venous access. The reason for this are concerns that vasopressors given over a peripheral venous catheter (PCV) may cause phlebitis or even worse necrosis or ischemia through extravasation. While irritation of a peripheral vein is often observed with the administration of drugs like potassium or amiodarone, this usually is not the case with the application of, e.g. norepinephrine. Besides, it is essential to keep in mind that the insertion of a central venous catheter (CVC) is technically demanding and takes a certain amount of time when performed correctly. The procedure is also associated with potentially dangerous complications that might be hazardous to the patient. Therefore a fundamental question arises: Do all patients that require vasopressors need a central venous catheter? What about the peripheral access (PVC) - Any dangers there?

|

Search

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed