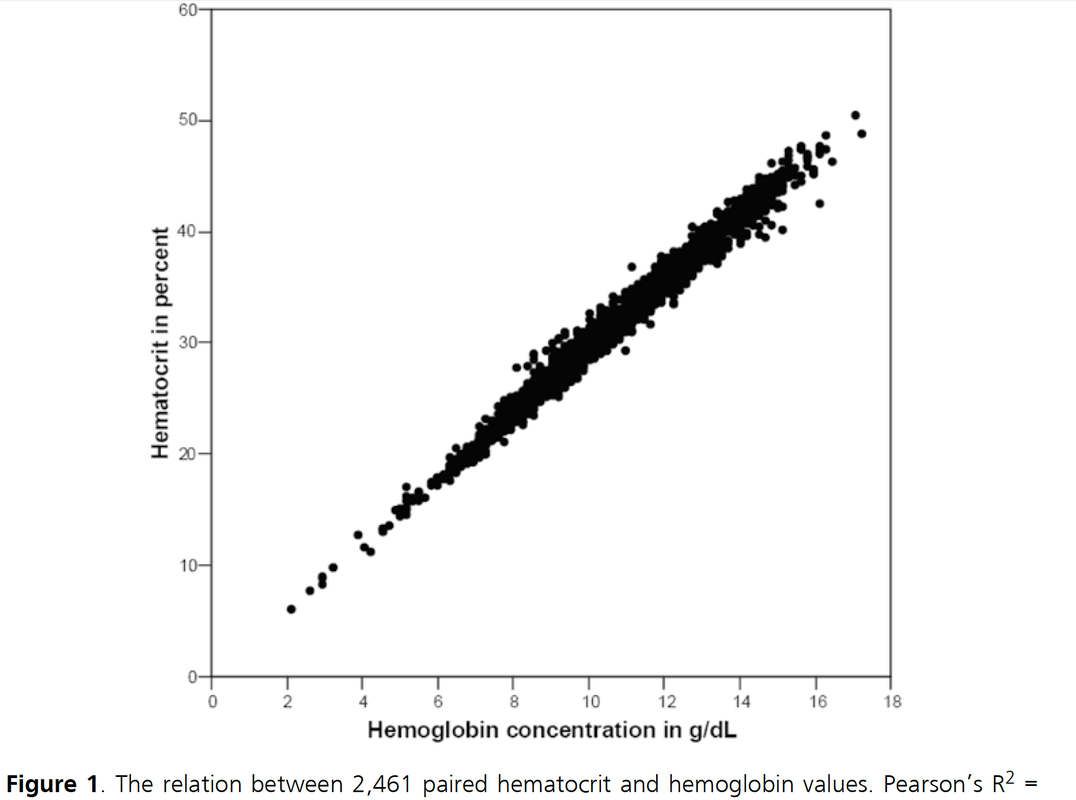

It starts in medical school, regularly appears in your medical training, sneaks around nursing schools and is an impetus for discussions in the ICU: The great myths about Hemoglobin (Hb) and Hematocrit (Hct). These two haematological lab-parameters are part of our daily life at work and are mostly measured together... as a package. Some clinicians look at haemoglobin levels, others prefer hematocrit levels... but then there is always someone making a great deal of differentiating between the two parameters and making all sort of diagnostic conclusions. 'Hct is better to determine dilution of the patient' or 'Acute blood loss is better determined by Hb than Hct'... and so on. So here's the question: What actually is the difference between Hb and Hct? Do we need to measure both in clinical practice? What's the difference? Hemoglobin levels are mostly measured by automated machines designed to perform different tests in blood. Within the machine, the red blood cells are broken down to get the haemoglobin into a solution. The concentration of haemoglobin is then measured by spectrophotometry using the methemoglobin cyanide method. Hematocrit levels in contrast are actually calculated by an automated analyzer... It is actually not measured directly! The analyser multiplies the red blood cell count by their mean corpuscular volume. What is Fact? There simply is NO difference between Hemoglobin and Hematocrit by means of clinical information!

Conclusion

Once and for all! Nijboer J et al. J Trauma. 2007;62(5):1310-2.

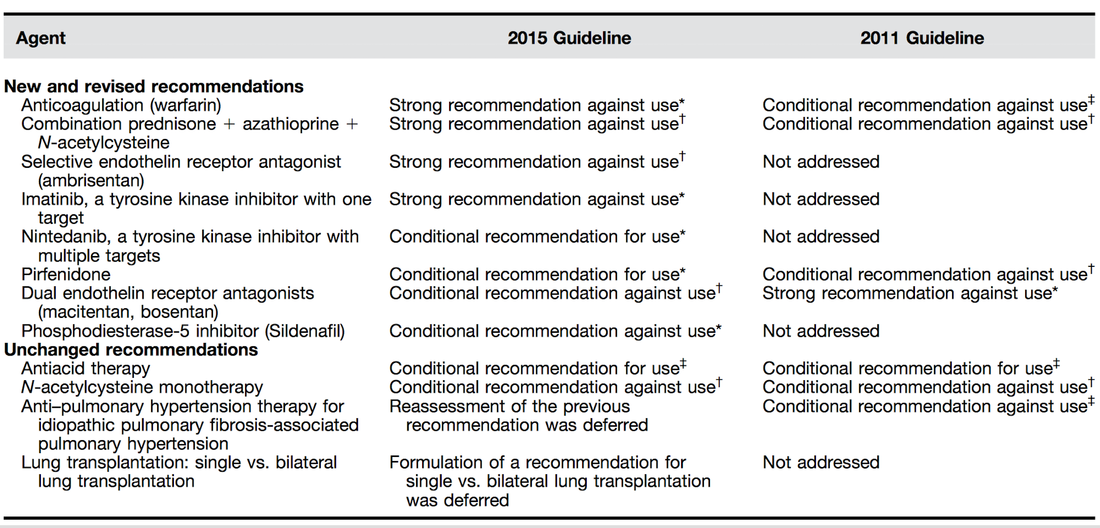

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is one of these frustrating diseases you repeatedly encounter in the ICU and that mostly leaves you sort of frustrated at the end. Despite all the efforts in research we are still left with very little we can do. This is one reason why also intensivists need to keep themselves updated on this topic. As knowledge is growing the ATS, ERS, JRS and ALAT (... thoracic and respiratory societies) made the effort to look into the latest evidence by performing systematic reviews and where appropriate meta-analyses. The aim was to update the guidelines published in 2011. These guidelines are also dedicated to Mr. William Cunningham who actively participated in the development of these guidelines, suffered from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis for many years and who was directly confronted with the issues related with this condition. The main conclusions can be briefly summarised as follows: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Update of the 2011 Clinical Practice Guideline, American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Vol. 192, No. 2 (2015), pp. e3-e19. OPEN ACCESS: Executive Summary 2015 An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Evidence-based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management, Am J Respir Crit Care Med Vol 183. pp 788–824, 2011 OPEN ACCESS For further information on acute exacerbations of IPF we recommend this Review Article:

When performing a kidney transplantation nowadays up to 50% of recipients developed a delayed graft function which is defined as the need of dialysis within seven days. The authors of this recently published NEJM-article asked themselves whether mild hypothermia might influence outcome in this regard. In order to answer this question the investigators assigned organ donors after declaration of death according to neurologic criteria into two groups. They were either treated with mild hypothermia (34 to 35°C) or with normothermia (36.5 to 37.5°C). The target temperature was maintained until the patients were transferred to theatre for transplantation. Primary outcome of this trial was delayed graft function among recipients. Secondary outcomes included the rates of individual organs transplanted into each treatment group at the total number of organs transplanted from each donor. This trial had to be stopped early as an interim analysis showed significant efficacy of mild hypothermia. Up to this point a total of 572 patients received a kidney transplant (285 in the hypothermia group and 287 in the normothermia group). 28% of recipients in the hypothemia group developed delayed graft function compared to 39% in the normothermia group. The authors therefore conclude that mild hypothermia significantly reduces the rate of delayed graft functions among recipients.

Anyhow, it seems reasonable not to get rid of your cooling devices!  Read more about the controversies of hypothermia in the ICU: The Targeted Temperature Management Trial: Nielsen N, et al. New Engl J Med. 2013 Dec;369(23):2197-206 The 2 trials that introduced therapeutic hypothermia into ICU practice: The Hypothermia After Cardiac Arrest Study Group, Holzer at al. New Engl J Med. 2002 Feb;346(8):549-556 Bernard S.A. et al. New Engl J Med. 2002 Feb;346(8):557-563 Review article on therapeutic hypothermia for non-VF/VT cardiac arrest: Sandroni S. et al. Crit Care Med; 2013;17:215 Pyrexia and neurological outcome: Leary M. et al. Resuscitation. 2013 Aug;84(8):1056-61 BIJC post on: The Effect of Pre-Hospital Cooling: Rather Worrying Results  Beverley Hunt at al. have just published an excellent practical guideline for the haematological management of major haemorrhage which also serves a a great educational review on this topic... an excellent piece of work! The authors look at this topic point for point and review current literature in an easy to understand sort of manor. They define major blood loss when it leads to a heart rte of >110/Min or a systolic blood pressure of less than 90mmHg, or simply said: when bleeding becomes haemodynamic relevant. In general it is recommended to have a major haemorrhage protocol at hand (1D) and all staff should be trained to recognise major blood loss early (1D). Here's a summary of the recommendations made by the British Committee for Standards in Haematology (BCSH): In Major Haemorrhage.... Red Blood Cells RBC - Hospitals must be prepared to provide emergency Group 0 red cells and group specific red cells (1C) - Patients must have correctly labelled samples taken before administration of emergency Group 0 blood (1C) - There is NO indication to request 'fresh' or 'young' red cells (under 7d of storage, 2B) - Note: The optimum target haemoglobin concentration (Hb) in this clinical setting in general is NOT established. Current literature shows a tendency towards restriction towards 70-90g/L, but the BCSH makes no recommendations therefore (see blow) Cell Salvage (e.g. cell saver) - 24h access to cell salvage should be available in cardiac, obstetric, trauma and vascular centres (2b) Haemostatic Monitoring - Use haemostatic tests regularly during haemorrhage, every 30-60min, depending on severity of blood loss (1C) - Measure platelet count, PT, aPTT (1C) - Note: The BCSG does not recommend TEG and ROTEM at this stage Fresh Frozen Plasma FFP - Use FFP in a 1:2 ratio with RBC initially (2C) - Once bleeding is under control administer FFP when PT and/or aPTT is >1.5 times normal (recommended dose 15-20ml/kg, 2C) - The use of FFP should not delay fibrinogen supplementation if necessary (2C) Fibrinogen - Supplement fibrinogen when levels fall below 1.5g/L Prothrombin Complex Concentrates PCC - Do not use PCC Platelets - Keep the platelet count >50 x 10^9/L (1B) - If bleeding persists give platelets if count falls below 100 x 10^9/L (2C) Tranexamic Acid TA - Give tranexamic acid as soon as possible to patients with, or at risk of major haemorrhage (Recommended dose: 1g IV over 10min, followed by 1g IV over 8h, 1A) - Note: TA has no known adverse effects - Note: Aprotinin is not recommended Recombinant Activated Factor VIIa (Novo Seven) - Do not use Specific Clinical Situations Obstetrics - Fibrinogen levels increase during pregnancy to 4-6g/L - In major obstetric haemorrhage fibrinogen should be given when levels are <2.0g/L (1B) GI-Bleed - Use restrictive strategy for RBC transfusion is recommended in most patients (1A) Trauma - Transfuse adult trauma patients empirically with a 1:1 ratio of FFP : RBC (1B) - Consider early use of platelets (1B) - Give tranexamic acid as soon as possible (Dose 1g over 10min and then 1g over 8h, 1A) Prevention of Bleeding in High-Risk Surgery - Use tranexamic acid (Dose 1g over 10min and then 1g over 8h, 1B) Hunt B et al. British J Haemat, July 6 2015 Read more HERE: Great Review on Transfusion, Thrombosis and Bleeding Management Restricitve Transfusion Threshold in Sepsis, the TRISS Trial Transfusion: Harmful for Patients Undergoing PCI? |

Search

|

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed