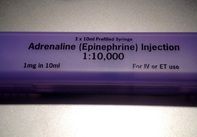

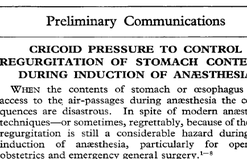

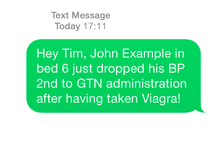

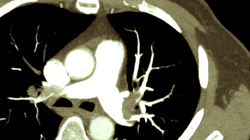

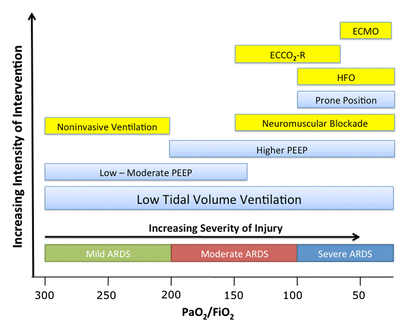

Guidelines on advanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation around the world, including the ACLS guidelines, are based on four important concepts: mechanical resuscitation (CPR), defibrillation, airway management and also application of vasoactive drugs. The application of these drugs is intended to improve hemodynamics and the heart's responsiveness to defibrillation. What some of us might not be aware of though, but has already been mentioned by the '2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations' and the 'European Resuscitation Council Guidelines' in 2010: There is actually no definitive evidence that the application of these drugs provides any long-term benefit for these patients. While vasopressors are intended to improve coronary and cerebral perfusion and therefore successful defibrillation and neurological outcome, there is actually some concern (animal and registry studies) that this might actually decrease microcirculation and cerebral blood flow as well as increase myocardial oxygen consumption and cause post-defibrillation ventricular arrhythmias. Also the use of anti-arrhythmic drugs as well as their combination with vasopressors lacks evidence of any impact on survival. Another interesting fact is that we have no idea about ideal dosage or optimal timing of these drugs... should they be given continuously? This and many more questions and facts are discussed in an interesting review article by Sunde and Olasveengen in Current Opinion in Critical Care. They conclude that there is no evidence to support any specific drugs during cardiac arrest and that healthcare systems should not prioritise implementation of unproven drugs before good quality of care can be documented. Are we heading towards an era of drug-free resuscitation? Sunde K et al. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014 April 16 Article accessible here  Most of us being trained as anaesthetists in the last couple of years have learnt to perform a rapid sequence induction (RSI) including the application of cricoid pressure (aka the Sellick manoeuvre) in order to prevent aspiration of gastric content. Over the last couple of years though this manoeuvre has been seriously questioned as scientific evidence is lacking and there are concerns that cricoid pressure might actually be potentially harmful. A lot has been written on this topic so far and some great reviews can be found easily on the internet thanks to the concept of Open Free Access Meducation (FOAMed, see below). Still I would like to add some thoughts on to this discussion and maybe mention one or two more interesting facts. Cricoid pressure was actually first described by Sellick in the Lancet in 1961 as a preliminary report and basically represented an un-controlled case study in which no or only insufficient information on the studies patient population was provided. There was no standardisation of the force for cricoid pressure as of the medications used for induction. There was also no information on the quality of laryngoscopy and intubation. Steinmann and Priebe (abstract in english) have exactly analysed this publication and found some relevant methodological shortcomings. It is therefore remarkable that this publication led to an anaesthetic dogma practised all over the world. As mentioned in the European Resuscitation Council Guidelines of 2005, studies in anaesthetised patients show that cricoid pressure impairs ventilation in many patients, increases peak inspiratory pressures and causes complete obstruction in up to 50% of patients depending on the amount of pressure applied (Petito, Lawes, Hartsilver, Allman, Hocking, Mac, Ho, Shorten). The incidence of a difficult intubation is significantly higher in preclinical emergency situations than in an elective theatre environment (Timmermann A et al. Resuscitation 2007;70(2):179-185). It is therefore possible, that cricoid pressure itself actually is one of the reasons why unexperienced emergency physicians experience additional difficulties when intubating 'in the field'. One concern often mentioned is the fear that non-adherence to current guidelines by not applying cricoid pressure might have adverse legal implications. But what do current guidelines actually say? Priebe et al. partially looked at this in 2012. Several guidelines indeed still recommend cricoid pressure, sometimes even with less force in the awake patient. But some guidelines have started to implement current evidence. The 2010 Clnical Practice Guidelines on General Anaesthesia for Emergency Situations by the Scandinavian Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine state following: (i) The use of CP cannot be recommended on the basis of scientific evidence (recommendation E, supported by non-randomized, historic controls, case series, uncontrolled studies and expert opinion) (ii) The use of CP is therefore not considered mandatory but can be used on individual judgement (recommendation E). (iii) If facemask ventilation becomes necessary, CP can be recommended because it may reduce the risk of causing inflation of the stomach (recommendation D, supported by non-randomized, contemporaneous controls) The 2005 European Resuscitation Council Guidelines (page 1322, pdf here) puts it this way: - The routine use of cricoid pressure in cardiac arrest is not recommended. - Studies in anaesthetised patients show that cricoid pressure impairs ventilation in many patients, increases peak inspiratory pressures and causes complete obstruction in up to 50% of patients depending on the amount of cricoid pressure (in the range of recommended effective pressure) that is applied. Still though it has to be mentioned that the Difficult Airwas Society (DAS) continues to recommend cricoid pressure for RSI on it's website. The current recommendation though seems to date back to 2004 and the question is mentioned on their website whether any pressure should be applied before loss of consciousness. Also the Association of Anaesthetists in Great Britain and Ireland recommends cricoid pressure in their AAGBI Safety Guidelines of 2009 on pre-hospital anaesthesia. It is also mentioned that 'badly applied cricoid pressure is a cause of a poor view at laryngoscopy. It may need to be adjusted or released to facilitate intubation or ventilation'. While the discussion on this issue in adults will continue the dogma of cricoid pressure might soon fall in paediatric patients as Neuhaus D et al. published a Swiss trial in 2013 where they could show that a controlled rapid sequence induction without cricoid pressure is actually safe. Further research is on its way: Trethrewy E et al. Trials. 2012 Feb 16;13:17. Until then it seems as if we are faced with guidelines mostly still in favour for cricoid pressure and evidence based medicine, which is rather discouraging us of further performing this procedure. It is good practice to constantly question current guidelines and further improve them for the patient's sake. Indeed you have to ask yourself on how far you want to stick to current guidelines for legal reasons or if you change your practice according to emerging evidence. Some of the hospitals I worked at in Switzerland have stopped performing cricoid pressure for RSI some years ago and haven't encountered any worsening in their patient outcomes. Taking into account that most RSI in the ICU resemble emergency intubations out of hospital rather than the controlled environment of a theatre I feel there are good reasons to start re-evaluating and possibly change current guidelines. Other very interesting resources of information can be found here (FOAMed): - lifeinthefastlane.com on cricoid pressure - resus.me on cricoid pressure - Update 02/05/14: Minh Le Cong published a statement of the NAP 4 investigators on his blog website: statement from NAP 4 (on prehospitalmed.com) ... The discussion goes on!  Many intensive care units try to avoid extubations at nighttime due to the fear of potentially fatal complications and possibly higher reintubation rates. However, it might actually be favourable to extubate patients as soon as possible, as this might have a positive impact on ventilation related complications and patient's length of stay. Interestingly nobody has ever looked at this special topic so far. Tischenkel BR et al. have now looked at this topic in a retrospective cohort study of two hospitals in the state of New York. In this paper, published in the Journal of Intensive Care Medicine this month, they looked at a total of 2240 patients which were extubated in intensive care units over the period of almost 2 years. As a result they could show that nighttime extubations did not have a higher likelihood of reintubation, length of stay or mortality compared to those during the day. They conclude that patients should be extubated as soon as they meet parameters in order to potentially decrease complications of mechanical ventilation. These data, they say, do not support delaying extubations until daytime. I fully agree... as long as there is somebody in the unit able to deal with potentially deleterious complications! Tischenkel BR et al. J Intensive Care Med April 24, 2014  Do you use text messages (sms) in your ICU? Of course you do... we all do! It seem sometimes a little worrying to see how text messaging has secretly creeped into clinical life in hospitals. Apart from simply talking to each other on the phone clinicians increasingly use text messaging to exchange patient informations. Recent revelations by whistleblowers like Edward Snowden have made us very aware of the fact that exchanged text messages can be easily intercepted and therefore read by a third party. The worst case scenario would be the publication of confident patient information. The chance, that patient information will leak in that sort of way is not very big, but 'Medical Identity Theft' happens and now slowly starts to find it's way into medical publications. The World Privacy Forum estimates, that 250'000 to 500'000 people have already been victimised by this sort of crime since 1995. So this kind of threat should be taken seriously. The Society of Critical Care Medicine has just recently published an article on this issue that nicely shows the different challenges we encounter by using all different sorts of mobile devices. Medical societies have not yet specifically given any recommendations on this topic, but it is clear that all private health information must be protected against any threat on confidentiality. The Joint Commission, an institution involved in the accreditation of medical institutions all around the world, gets very specific on the use of text messages: “Physicians who need to quickly communicate time-sensitive information about their patients should no longer use text messages.” So what can we do in clinical practice? One option is to start using encrypted services (e.g. Threema). But then again technical issues between different sort of mobile devices might be problematic. And different people might use different applications. The question remains if simple text messages can be considered safe by simply using de-identified information. What do you do in your hospital...? Christine C. Toevs, SCCM on Communication, February 2014  It has been almost for 40 years that the positive effect of prone positioning in ARDS patients was recognised. But even up to 2012 no benefit on mortality could be found in several studies and also the duration of prone positioning was not found to make any difference. In June 2013 Guerin et al. published the PROSEVA trial which indeed showed some amazing results. It is the 5th biggest trial of it's kind and finally was able to actually now show a dramatic reduction in mortality: the 28 day mortality was 32.8% in the supine group (229 patients), compared to only 16% in the prone group (237 patients). This benefit in outcome persisted also after 90 days... a miracle? Most probably these results reflect the very strict adherence to the guidelines of ARDSnet in regards of paralysation and use of very low tidal volumes. One thing that has to be mentioned is the high number of patients with ARDS which have excluded from the trial for several reasons. So should we now follow this study and prone more aggressively? One answer might be the just recently published meta-analysis by Lee at al. in Critical Care Medicine. This paper looked at a total of 11 randomised controlled trials and therefore takes all recent publications into account. The authors come to the conclusion that prone positioning indeed does reduce mortality significantly and were marked in the subgroup where the duration of prone positioning was more than 10 hours. This is the first time somebody actually comments on the length of prone positioning in terms of benefit for the patient. As always though there are also adverse effects of this therapy as prone positioning was significantly associated with pressure sores and maybe most importantly major airway problems. Overall, the concept of prone positioning in severe ARDS seems to be well established and should be implemented in the clinical procedures of every intensive care unit. This is particularly true for regions where quick access to extra corporal CO2 removal or oxygenation devices is difficult. Guerin C et al. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jun 6;368(23):2159-68. Lee JM et al. Crit Care Med. 2014 May;42(5):1252-62. Ferguson et al. Intensive Care Med. 2012 Oct;38(10):1573-82. A very nice and quick overview on treatment options for ARDS was presented by Ferguson et al. in Intensive Care Medicine 2012:  On the 21st of February this year we mentioned a paper by Sharifi et al. who introduced a new concept of 'Safe Dose Thrombolysis'. Background is the fact that for most patients, e.g. intermediate risk pulmonary embolism (PE), thrombolysis is not recommended due to the risk of bleeding. The question though remained wether intermediate risk patients actually also would benefit of thrombolysis in terms of outcome. In the recent NEJM now a trial is presented where the investigators focused on exactly this so called 'intermediate risk' group of patients. They randomized 1005 patients with PE who had right ventricular dysfunction on echocardiography or computed tomography, as well as myocardial injury as indicated by a positive test for cardiac troponin I or troponin T. The one group received tenecteplase and heparin, the other only heparin. Result: Thrombolysis prevented hemodynamic decompensation and death... but at the same time increased the risk for major hemorrhage and stroke. What a dilemma! That's where I feel 'Safe Dose Thrombolysis' might be interesting to look at. Now there's a good topic for your next publication in the NEJM, go for it! (and please don't forget to mention us for the great idea ; ) Meyer G et al. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1402-1411 Sharifi M et al. Clin Cardiol. 2014 Feb;37(2):78-82  Most of us are aware of the medical leaflet warning that beta blockers in bronchospastic disease should be avoided or at least be given with great caution due to the risk of increased airway resistance. An interesting question therefore is, whether beta blockers prescribed in COPD patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) also benefit of their effect and if this also affects survival. Quint et al. have looked into this topic by performing a retrospective study including 1063 COPD patients, who experienced their first AMI. 55.1% of these patients were never prescribed a beta blocker throughout the study period, 23% were on beta blockers before and 21.9% were prescribed a beta blocker during their hospital admission for AMI. Patients started on beta blocker during their hospital admission showed substantial survival benefits compared to patients who were not prescribed any beta blockers. Patients taking beta blockers before their first myocardial infarction also showed a substantial survival benefit! Taking into the account these results and the increasing evidence that beta blocker are actually safe in COPD patients suggests that beta blockers should be used more widely in patients at risk for AMI. At least we should not be too worried to prescribe them. Quint J K et al. BMJ 2013;347:f6650 Dransfield M T et al. Torax 2008;63:301-305  Did you know that historically myocardial events happen most often on mondays? Sandhu et al. have now looked at what actually happens when time is changed to daylight savings time (DST, or summer time). The researchers looked at a total of 42'060 patients admitted with heart attacks requiring percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) during the period of January 1st 2010 until September 15th 2013. All patients were admitted to hospitals in the state of Michigan in the U.S. The results they found were surprising. On the monday after changing to DST (summer time) there was an increase of 24% in daily acute myocardial infarction (AMI) counts! The total number of AMI's during the following week though remained the same. Interestingly now when changing back to standard time (winter time) the following tuesday showed a 21% drop in AMI, that's when we get our hour back. Their conclusion was: In the week following the seasonal time change, DST impacts the timing of presentations for AMI but does not influence the overall incidence of this disease. Did you know that all this time changing was widely introduced during the first world war in order to save energy. The impact on saving energy nowadays is highly debatable, but more and more evidence arises that the impact on humans (and animals) is more pronounced than expected. Another reason to stop this silly habit once and forever! Open Heart 2014;1: doi:10.1136/openhrt-2013-000019 |

Search

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed