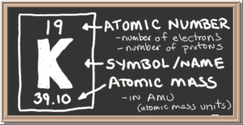

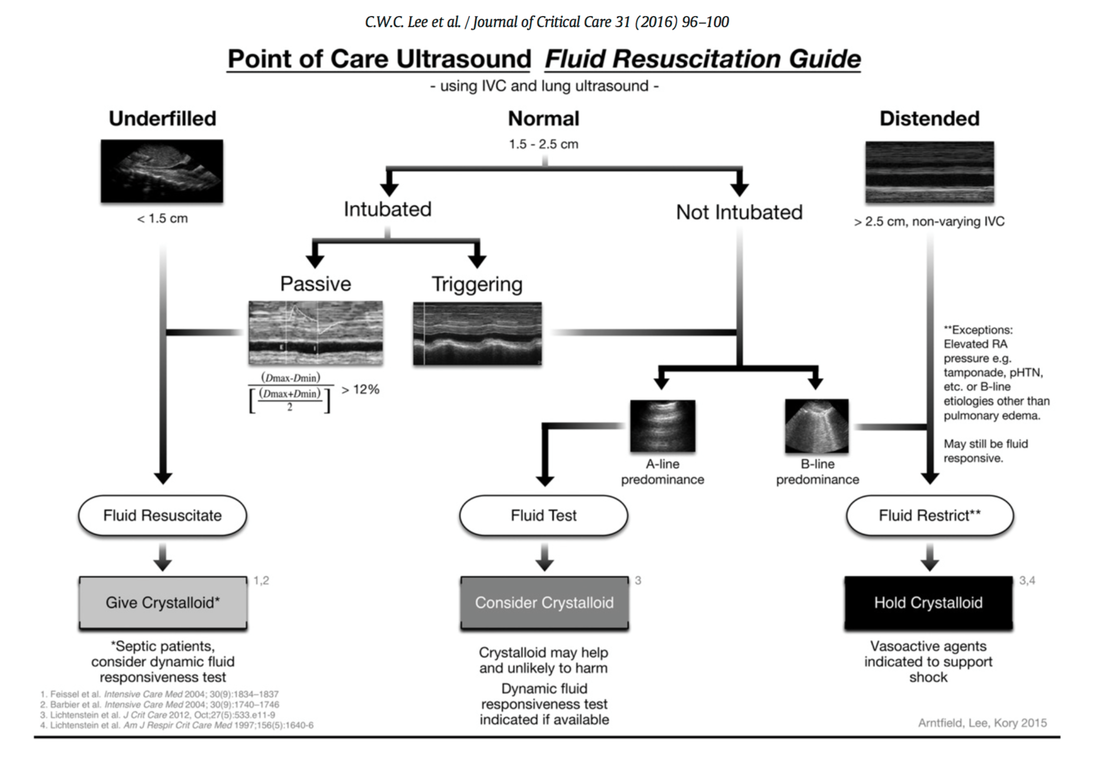

Fluids are one of the cornerstones in the treatment of patients with shock. But with any drug applied, also fluids can harm if given inappropriately! While inadequate fluid resuscitation might result in tissue hypoperfusion and worsening of end-organ function, to much fluid might lead to problems like pulmonary oedema and finally increased mortality. Many measures are used in clinical practice, but most of them lack specificity and are not very representative as a sole marker. One of the better methods to evaluate fluid requirements is the use of dynamic measures that estimate the change in cardiac output (CO) in response to a fluid bolus. In this regard the use of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has become increasingly attractive in order to use basic critical care ultrasound to asses the need of fluids in a specific clinical setting. Lee at al. have now looked at the sonographic assessment of the inferior vena cava and lung ultrasound in order to quite fluid therapy in intensive care. By taking into account current evidence they have produced an algorithm using these measures to help guiding fluid therapy. As with any measurement in critically ill patients the pathophysiologic cause of shock must be taken into account. The algorithm presented here seems to work best in patients in hypovolemic shock. To fully understand the following algorithm and its limitations we recommend to read the open access article (see link below). In conclusion: The algorithm provided is a helpful tool to help assess the need of fluids in a simple and quick manner. Lee C et al. J of Crit Care 31 (2016) 96-100 OPEN ACCESS  Just recently the discussion came up once again on what sort of infusion should be used in patients with hyperkalemia. To my surprise the idea seems to persist that normal saline (NS) should be used, as this solute does not contain any further potassium. This is a thought in the wrong direction and Pulmcrit made a great statement in 2014 to clarify this myth. The key points are as follows:

Here's all the background reading including references: Pulmcrit Myth-busting: RL is safe in hyperkalemia, and is superior to NS This might also be of interest. Have a very close look on normal saline infusions: Normal Saline and Acidosis: Is it Really the Salt that Matters?  Again we have picked a review article looking at fluid resuscitation in the ICU. This article by Lira et al. in the Annals of Intensive Care looks at all the new literature available in regards of fluid therapy during resuscitation. Also review current recommendations and recent clinical evidence. This results in an excellent systematic review that leaves us with following conclusions: - Currently no indications exist for the routine use of colloids over crystalloids - In regards of current evidence (including the Albios trial), the cost and limited shelf time the use of albumin as a resuscitation fluid is not recommended - The use of hydroxy-ethyl-starch (HES) during resuscitation should be avoided - In light of the lack of evidence, and the theoretical potential for adverse effect, the suggestion is to avoid gelatine or dextran - The use of 0.9% normal saline is associated with the development of hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis and increased risk of AKI in susceptible patients. Therefore balanced crystalloid solutions should be considered/ preferred - Current literature supports the use of balanced crystalloid solutions (e.g. Hartmann's solution, Ringer's lactate) whenever possible This makes things quite simple actually... but of course opinions differ! Lira and Pinsky, Annals of Intensive Care Dec 2014, 4:38 OPEN ACCESS Read here: The Albios trial  As published in the New England Journal the ALBIOS trial has already received a lot of attention and was also one of the hot topics at the ISICEM in Brussels last week. So what’s the story. First there is the original article published in the recent NEJM. Gattinoni et al. have looked into the potential advantages in giving 20% albumin and cristalloid solutions to hypoalbuminic patients with severe sepsis compared to cristalloid solutions only. In the albumin group they aimed for a serum albumin concentration of 30g/L (a number hardly ever seen in any ICU patient) until discharge from the ICU or 28 days after randomization. 1818 patients were included and to make things short: The trial found no difference in 28-day mortality (primary outcome), 90-day mortality (secondary outcome), or any other relevant clinical endpoint (number of patients with organ dysfunction, degree of dysfunction, length of stay in ICU and the hospital). So far for the original article. But now there is also this wonder-some supplementary appendix where the group has performed an unplanned subgroup analysis in septic shock patients only where a significant difference in the 90-day mortality was found - in favor for albumin. Indeed there is a lower number of deaths in the albumin group, but not in the p value when adjusted for clinically relevant variables. It might also be interesting to note that the 90-day mortality was a secondary endpoint and no subgroup analysis was performed of 28-day mortality among patients with septic shock. My personal view on this topic is that the original article and the supplemental appendix provide no good reason to favor albumin in the treatment of septic patients in general. The evidence provided to support the application of hypertonic albumin in septic shock patient is also not very convincing. In regards of the SAFE study from 2004 the use of albumin will remain controversial and it will be interesting to see further trials upcoming in this field. It is also worthwhile remembering that albumin remains reasonably expensive and as Prof. Takala, Bern Switzerland, mentioned in Brussels last week: the money saved on avoiding unnecessary albumin infusions might be better invested in other ICU resourced proven to improve patient outcome. Comments? Gattinoni L et al. N Engl J Med March 18, 2014 Gattinoni L et al. N Engl J Med March 18 2014: Supplemental Appendix SAFE study. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:2247-2256 Iodinated Radiocontrast Agents can cause Kidney Injury... But not as much as we thought they would!12/3/2014

One major concern when bringing a critically ill patient for a CT scan is the potential for acute kidney injury (AKI) by applying iodinated contrast media intravenously. Post-contrast AKI carries the risk of more permanent renal failure, dialysis and even death. The authors of this review article nicely summarize current evidence on this issue and show, that the risk of AKI secondary to contrast material (particularly when administered intravenously for contrast-enhanced CT) has been exaggerated in the past by older, noncontrolled studies. In fact, by reviewing more recent evidence they come to the conclusion that the risk is almost nonexistent in patients with normal renal function. Even in patients with pre-existing renal insufficiency the risk of secondary contrast-induced AKI is probably much smaller than traditionally assumed. Again they emphasize on the fact that volume expansion is the only preventive strategy with a convincing evidence base. Nevertheless, the benefits of a contrast-enhanced exam still will have to be balanced with the remaining risk of AKI. BioMed Research International. 2014, Article ID 859328  The transfusion of red blood cells in the ICU remains a hot topic not only since the CRIT study and TRICC trial. It has been associated with complications and worse outcome. Unfortunately anemia and bleeding are common problems in critical care and therefore transfusions remain an important tool in the treatment in these patients, especially as we know that anemia itself is harmful. The question still remains when and in which situations RBC transfusions are indicated and helpful, especially in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD). The TRICC trial in the NEJM in 1999 concluded: ‘A restrictive strategy of red-cell transfusion is at least as effective as and possibly superior to a liberal transfusion strategy in critically ill patients, with the possible exception of patients with acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina’. The clinical practice guidelines from the AABB in 2012 noted that they can not recommend for or against a liberal or restrictive transfusion threshold for stable patients with acute coronary syndrome Now JAMA addresses the issue of transfusion in patients with CHD undergoing percutaneous intervention (PCI). In this retrospective cohort study they looked at 2’258’711 patients (now that’s a number) in 1431 hospitals who underwent PCI in a period of almost 4 years. Despite a considerable variation on blood transfusions practices among these US hospitals, the receipt of transfusion was associated with increased risk of in-hospital cardiac events (myocardial infarction, stroke and hospital death). ... another puzzle piece towards restriction? Sherwood M et al. JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;Vol 311, No.8 Look up here: The TRICC trial and the CRIT study (the ‘need to know’s) A short educational overview can be found here: http://lifeinthefastlane.com/education/ccc/blood-transfusion-in-icu/ Clinical Practice Guidelines from the AABB 2012: Ann Inten Med. 2012;157:49-58 Clinical Practice Guidelines 2009: Red blood cell transfusion in adult trauma and critical care, Crit Care Med 2009  Intensivists have repeatedly been warning on the potential effect side effects when infusing bigger quantities of normal saline like acidosis and potentially worse outcomes. It is well recognized that infusion of normal saline can lead to metabolic acidosis, but the link between the acidity of saline solution and the acidaemia it can produce might be not straightforward! This article from the beginning of this year shows a surprising insight on the various components involved when using normal saline infusions and comes to the conclusion that the acidaemia complicating saline infusions is actually unrelated to the acidity of the normal saline solution itself. It turns out that in vitro the acidity of a normal saline solution is mainly due to dissolved CO2 and PVC degradation of the bag containing the solution. The metabolic acidosis by saline infusions in vivo though mainly results from from buffer base dilution and is not directly related to the pH of the infusion at all. Got interested? Reddi B, et al. Int J Med Sci. 2013 Apr;10(6):747-50 |

Search

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed