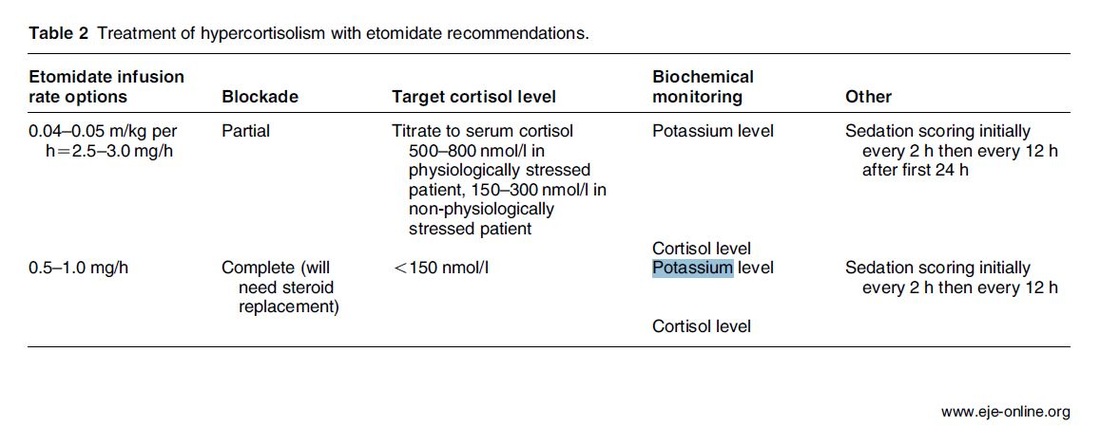

The Problem An endogenous Cushing's syndrome, mostly caused by an adenoma of the pituitary gland, is associated with significant morbidity and mortality when left untreated. The condition is closely associated to life-threatening infections, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and increased risk associated with surgery. For Cushing's disease the first line therapy is surgical removal of the pituitary tumor. Sometimes though urgent medical therapy is needed first. It has been shown, that surgical risk may be significantly reduced if cortisol concentrations are normalised preoperatively. Conditions requiring urgent cortisol-lowering measures are severe biochemical disturbances (e.g. hypokalaemia), immunosuppression or mental instability. Medical Treatment OptionsKetokonazole (yes, the antifungal agent) and metyrapone are used to suppress adrenal steroidogenesis at enzymatic sites. Both agents carry the risk of postential side effects. Mifepristone, a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, and pasireotide, a new targeted pituitary therapy, are alternative agents. However, they also have their limits and side effects. EtomidateNow that's where etomidate joins the game. Interestingly, etomidate and ketokonazole are chemically closely related... they are both members of the imidazole family. Etomidate is used as an anaesthetic agent since 1972 and became popular for hemodynamic stability and the lack if histamine release. In 1983 a Lancet article noted an increased mortality when etomidate was used in critically unwell patients. In 1984 an article in Anaesthesia first showed a link to low serum cortisol levels caused by etomidate. Until now the discussion continues, whether a single induction dose actually negatively influences patient outcome. A meta-analysis in 2010 was unable confirm this apprehension and the debate continues. Fact isEtomidate suppresses the production of cortisol by inhibiting the mitochondrial cytochrome p450-dependent adrenal enzyme 11-beta-hydroxylase and therefore lower serum cortisol levels within 12 hours. In higher doses it also blocks side chain cleavage enzymes and also aldosterone synthase. It might even have anti-proliferative effects on adrenal cortical cells. On this basis the idea arose, that etomidate might be a useful therapy for severe hypercortisolaemia. Continuous Etomidate - What's the EvidenceA review article by Preda et al. in 2012 identified 18 publications about the primary therapeutic usage of etomidate in Cushing's syndrome, most of which were case reports. Review of current literature reveals that etomidate indeed suppresses hypercortisolaemia safely and efficiently in patients requiring parenteral therapy. Moreover, etomidate shows a dose-dependent suppression and allows adjustment of the medication to target cortisol levels. At recommended dosages etomidate is considered safe with almost no serious side effects. The authors conclude, that etomidate is a useful therapeutic option in a hospital setting when oral therapy is not tolerated or inappropriate. Take home- Continuous etomidate (in non-hypnotic doses) reduces cortisol concentrations in a dose-dependent manner in both hyper- and eucortisolaemic subjects

- The application of continuous etomidate in Cushing's disease is safe and efficient - After termination of infusion adrenocortical suppression persists for about 3 hours - The suspicion, that a single dose of etomidate for rapid sequence inductions might negatively influence patient outcome in the critically ill remains a matter of debate J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990 May;70(5):1426-30. Preda et al. European Journal of Endocrinology (2012) 167 137-143 OPEN ACCESS Soh et al. Letter to the Editor, European Journal of Endocrinology (2012) 167 727–728 Ge et al. Critical Care201317:R20 OPEN ACCESS  Already years ago it has been noticed that stress and severe injury results in insulin resistance among ICU patients. This also occurs in patients who had no diabetic problems before an insult. Van den Berge et al. therefore postulated that an intensive glucose control in ICU patients would be of benefit. And indeed, in 2001 they published the well known article on intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. They showed that a tight glucose control results in reduced morbidity and mortality (by 42%) among ventilated, critically ill patients in surgical intensive care units (1548 patients included). Unfortunately though some clinical trials since have failed to reproduce this benefit of tight glucose control. A meta analysis in JAMA 2008 looked at 28 randomized controlled trial with a total of 8432 patients and found that tight glucose control was not associated with significantly reduced hospital mortality but an increased risk of hypoglycemia. The multinational NICE-SUGAR trial, including 6104 patients, finally made an end to tight glucose control on most ICU’s around the world. Against expectation mortality in the intensive-control group was higher as well as severe hypoglycemia. No difference though was observed in regards of length of stay in ICU, duration of hospitalization, days of mechanical ventilation, rate of pos. blood cultures and RBC transfusion. This month Kalfon et al. add another puzzle piece to this ongoing discussion with an article published in Intensive Care Medicine. This multi-center randomized trial included 2648 patients who were randomly assigned to tight computerized (CDSS) glucose control or conventional glucose control. And guess what: tight glucose control did not change 90-day mortality but was associated with more frequent severe hypoglycemia... In summary: there is not much in favor for tight glucose control coming up and there’s no need to invest in more expensive computers... Sweet! Kalfon P. et al. Intensive Care Med. 2014 Jan 14 van den Berghe, G. et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 1359–1367 (2001) NICE-SUGAR study investigators. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1283–1297 (2009) Wiener, R. S., Wiener, D. C. & Larson, R. J. Benefits and risks of tight glucose control in critically ill adults: a meta-analysis. JAMA 300, 933–944 (2008) |

Search

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed