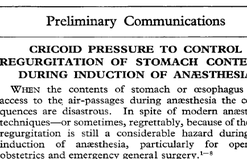

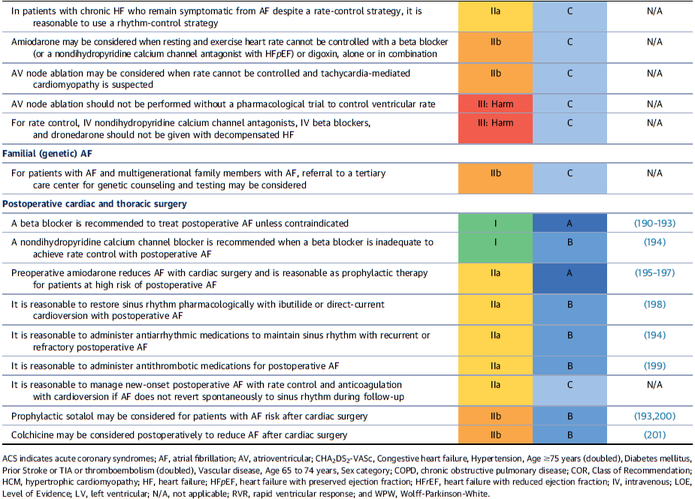

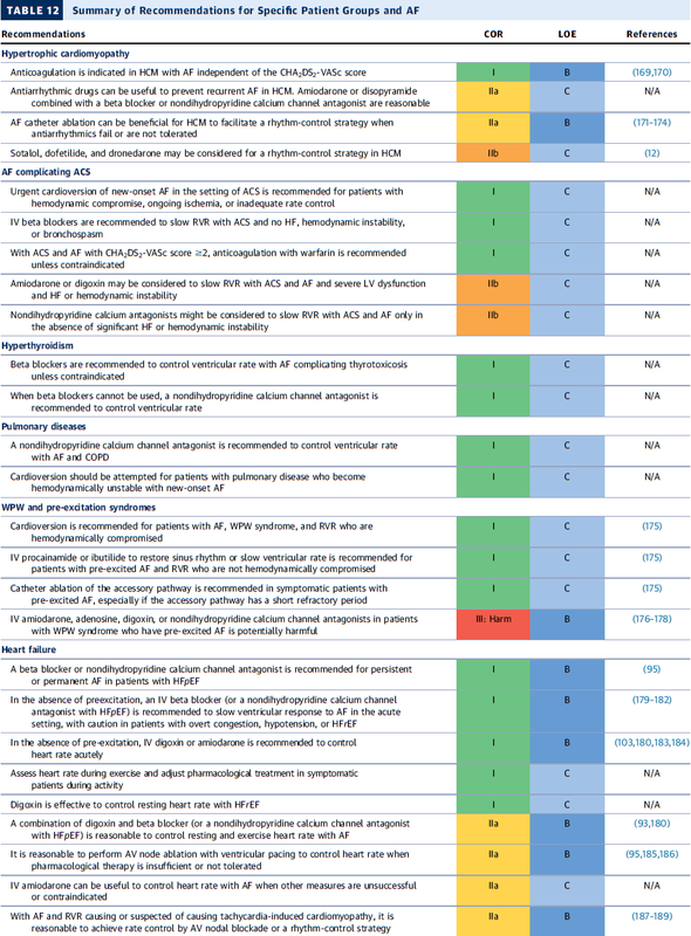

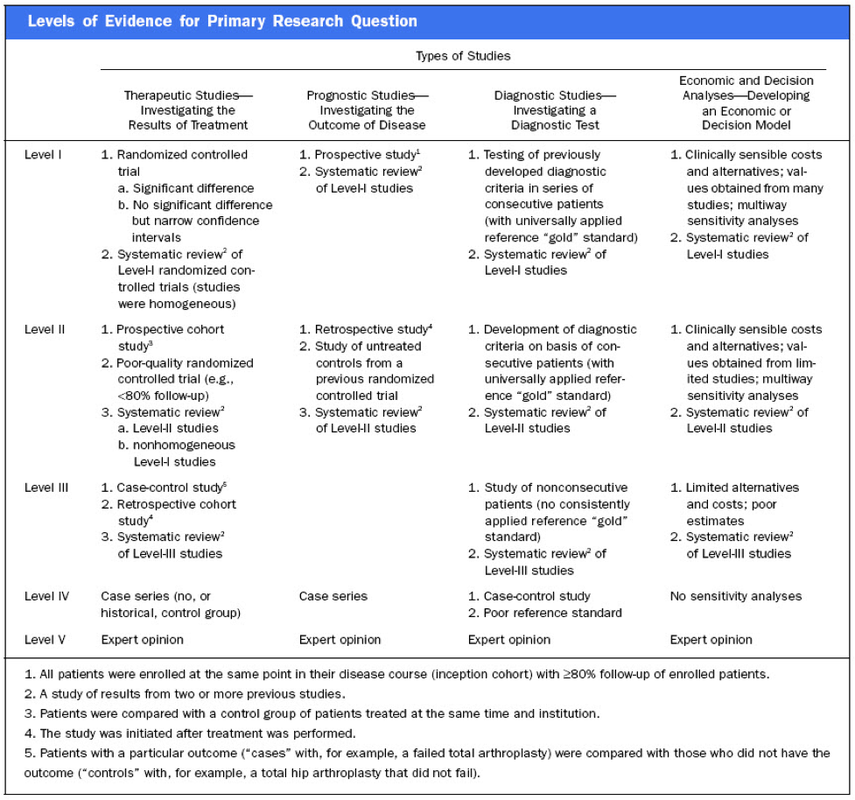

As every child already knows by now the study by Rivers et al. in 2002 has raised the awareness about sepsis and led to the establishment of the surviving sepsis campaign. As we have posted on BIJC before, many elements of the early goal directed therapy (EGDT) have been discussed controversially since. In order to answer some of the questions of sepsis treatment three big trials have been started, involving different parts of this world. These efforts have led to a unique situation as we now have three high quality trials looking at the classical EGDT versus 'usual care'. ARISE and ProCESS had been published before (read here) and both of them showed no difference between EGDT and 'usual care'. ProMISe included 1251 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock that were admitted to a total 56 hospitals in the UK. Again classical EGDT with measurement of continuous central venous oxygenation was compared to so called 'usual treatment'. It's remarkable to notice that in the 'usual treatment' group about half of the patient didn't get a central line and central venous oxygenation wasn't even measured in the ones who got one. And here's the result: There was no difference in 90-day mortality and no differences in secondary outcomes. In contrast EGDT actually increased costs. It has become difficult to ignore these three trials! Our conclusion: The classical EGDT therapy has ended here and now... but EGDT will keep its central role in the treatment of septic patients! Early: - Identify septic patient quickly, start screening for patients if indicated - Administer antibiotics within the first our of recognition of sepsis - Start IV-fluid therapy immediately - Take (blood) cultures as quick as possible, but do not delay antibiotic treatment Goal Directed: - Aim for a reasonable mean arterial pressure (e.g. 65mmHg) - Aim for a sufficient urinary output (0.5ml/h) - Central venous pressure (CVP) certainly and most probably central venous oxygenation (ScvO2) are not parameters to measure fluid responsiveness - Lactate remains an issue of debate Therapy: - Simple: Whatever the physician feels is best! ProMISe Trial, Mouncey et al. N Engl J Med. 2015 Mar 17. BIJC Review on ARISE and ProCESS Picture displayed taken from the Ice Cream Trilogy by Wright, Pegg and Frost  In December 2014 the AHA, ACC and HRA have released a new bunch of guidelines on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib). The paper itself is worth reading as it looks into the basic understanding of this condition, its clinical evaluation and finally the treatment options. As these guidelines are open access it can be considered mandatory Free Open Access Meducation FOAMed. Below is a summary of the Recommendations according to specific patient groups. It's interesting to notice that digoxin still plays a role in patients with heart failure, especially when looking at the findings of Turakhia et al. in JACC, Aug 19 2014. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(21):2246-2280 OPEN ACCESS BIJC post on dixogin in critical care  'Anaesthesia', the Journal of the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland have published an Open Access Supplement on various aspects of Transfusion, Thrombosis and Bleeding Management. This is an excellent opportunity to update your knowledge in this field and actually compulsory for anyone involved actively in critical care. The supplement consists of multiple review articles which are kept nice and short and are perfect for reading in between... In Conclusion: Reading highly recommended! On following website you can find a list of all articles including links to the full text: Anaesthesia, Vol. 70, Issue Supplement s1, January 2015: Transfusion, Thrombosis and Bleeding Management  Platelets are used in critical to either prevent or treat bleeding. The problem is that despite all the research and studies we still don't know that much on the best way to clinically use platelets... and they are tricky indeed: - Platelets must be stored at room temperature - Because of the risk of bacterial growth the shelf life of platelet units is only 5 days - Maintaining a constant pool of platelets for clinical work is extremely difficult and resource-intensive - Transfusion related risks are notable (e.g. febrile reaction 1/14, allergic reactions 1/50, bacterial sepsis 1/75'000) When it comes to their usage intensivists often have a different approach than haematologists and guidelines mostly vary from hospital to hospital, from country to country. However, instead of searching all the literature yourself you might consider reading the article by Kaufman RM et al. published just this month in the Annals of Internal Medicine. A panel of 21 specialists, covering almost all areas of medicine involved in handling platelets, performed a systematic review by looking up publications from 1900 to 2013. From 1024 identified studies, 17 RCTs and 53 observational studies were included in the review. The result of their work are guidelines on the use of platelets including their grade of recommendation. Short: - Platelets should be transfused prophylactically to reduce the risk for spontaneous bleeding in hospitalized adult patients with therapy-induced hypo proliferative thrombocytopenia < 10 x 109 cells/L (Grade: strong recommendation; moderate-quality evidence) - Platelets should be transfused prophylactically for patients having elective central venous catheter placement with a platelet count less than 20 × 109 cells/L (Grade: weak recommendation; low-quality evidence) - Prophylactic platelet transfusion is recommended for patients having elective diagnostic lumbar puncture with a platelet count less than 50 × 109 cells/L (Grade: weak recommendation; very low-quality evidence) - Prophylactic platelet transfusion is recommended for patients having major elective nonneuraxial surgery with a platelet count less than 50 × 109 cells/L (Grade: weak recommendation; very low-quality evidence) - Routine prophylactic platelet transfusion for patients who are nonthrombocytopenic and have cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is NOT recommended. Platelet transfusion for patients having CPB who exhibit perioperative bleeding with thrombocytopenia and/or evidence of platelet dysfunction is NOT recommended (Grade: weak recommendation; very low-quality evidence) - Recommendations for or against platelet transfusion for patients receiving antiplatelet therapy who have intracranial hemorrhage (traumatic or spontaneous) cannot be made (Grade: uncertain recommendation; very low-quality evidence) It is remarkable to see that after a century of intense research we are left with some moderate-quality evidence and lots of low quality evidence and therefore weak recommendations. I guess guidelines will continue to vary from doctor to doctor, hospital to hospital... country to country. Kaufman RM et al. Ann Intern Med, Nov 11, 2014: Open access article  As mentioned in one of our earlier entries two important trials (Hermanns et al. The Lancet and Caesar et al. NEJM) have indicated that early parenteral nutrition (PN) might actually be harmful and a late PN strategy should be the standard of care. Despite this the debate has continued and remains highly controversial. This is nicely reflected in recent guidelines regarding the timing of supplemental PN. While the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) recommends PN within 24-48h in patients who are expected to be intolerant to enteral nutrition (EN), the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) recommends postponing the initiation of PN until day 8 after ICU admission. In order to clarify things a little Bost et al. have now published a systematic review on the timing of parenteral nutrition in critical care (Open access). From 3520 initially screened articles only four randomised controlled trials and two prospective observational studies remained after critical appraisal. "In conclusion it seems to be reasonable to assume that in critically ill patients, when full enteral support is contraindicated or fails to reach caloric targets, there are no clinically relevant benefits of early PN compared to late PN with respect to morbidity or mortality end points. Considering that infectious morbidity and resolution of organ failure may be negatively affected through mechanisms not yet clearly understood and acquisition costs of parenteral nutrition are higher, the early administration of parenteral nutrition cannot be recommended." The Review in one short sentence: Early PN has no advantage over late PN, but might be actually harmful. Bost et al. Annals of Intensive Care 2014, 4:31 Read more: ESPEN Guidelines on parenteral nutrition, 2009 A.S.P.E.N. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient BIJC.org on: Starting early PN weakens the critically ill  In the most recent edition of 'Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care and Pain' there is a very good overview article on rapid sequence induction (RSI) and its place in modern anaesthesia. Wallace and McGuire also critically look at cricoid pressure (CP) as a part of classical RSI. In their publication they state that "there have been no prospective randomized clinical studies performed to prove the clinical hypothesis and the level of evidence to support the use of cricoid pressure is poor (Level 5)". Level 5 corresponds to 'Expert Opinion' (see table below). They also mention that aspiration has occured despite CP, that CP is often poorly performed, that it may hinder bag-valve mask ventilation as well as LMA insertion and that is may worsen laryngoscopy. It's mentioned that "Critically, it has also been shown to potentially obstruct the upper airway and reduce time to desaturation". 'This is nothing new' you might say. Why am I mentioning this? Well, the remarkable thing about this article is the fact that it was published in a Journal that is a joint venture of the British Journal of Anaesthesia BJA and The Royal College of Anaesthetists in collaboration with the Intensive Care Society and Pain Society. Considering the fact that The NAP4 guidelines continue to support its use as part of an RSI and as such, it is still considered a standard of care in the UK and therefore also Ireland, this publication might indicate some change in mind... or not? The authors summarize: Application of cricoid pressure is advisable — unless it obscures the view at laryngoscopy or interferes with manual ventilation or supraglottic airway device placement. I personally still would want to know what exactly makes a 'Level 5' medical intervention 'advisable' especially in regards of all the possible problems and complications associated with it. Wallace et al., Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain, Volume 14(3), June 2014, p 130–135 Read our previous BIJC post: Cricoid Pressure for RSI in the ICU: Time to Let Go? (Updated)  Most of us being trained as anaesthetists in the last couple of years have learnt to perform a rapid sequence induction (RSI) including the application of cricoid pressure (aka the Sellick manoeuvre) in order to prevent aspiration of gastric content. Over the last couple of years though this manoeuvre has been seriously questioned as scientific evidence is lacking and there are concerns that cricoid pressure might actually be potentially harmful. A lot has been written on this topic so far and some great reviews can be found easily on the internet thanks to the concept of Open Free Access Meducation (FOAMed, see below). Still I would like to add some thoughts on to this discussion and maybe mention one or two more interesting facts. Cricoid pressure was actually first described by Sellick in the Lancet in 1961 as a preliminary report and basically represented an un-controlled case study in which no or only insufficient information on the studies patient population was provided. There was no standardisation of the force for cricoid pressure as of the medications used for induction. There was also no information on the quality of laryngoscopy and intubation. Steinmann and Priebe (abstract in english) have exactly analysed this publication and found some relevant methodological shortcomings. It is therefore remarkable that this publication led to an anaesthetic dogma practised all over the world. As mentioned in the European Resuscitation Council Guidelines of 2005, studies in anaesthetised patients show that cricoid pressure impairs ventilation in many patients, increases peak inspiratory pressures and causes complete obstruction in up to 50% of patients depending on the amount of pressure applied (Petito, Lawes, Hartsilver, Allman, Hocking, Mac, Ho, Shorten). The incidence of a difficult intubation is significantly higher in preclinical emergency situations than in an elective theatre environment (Timmermann A et al. Resuscitation 2007;70(2):179-185). It is therefore possible, that cricoid pressure itself actually is one of the reasons why unexperienced emergency physicians experience additional difficulties when intubating 'in the field'. One concern often mentioned is the fear that non-adherence to current guidelines by not applying cricoid pressure might have adverse legal implications. But what do current guidelines actually say? Priebe et al. partially looked at this in 2012. Several guidelines indeed still recommend cricoid pressure, sometimes even with less force in the awake patient. But some guidelines have started to implement current evidence. The 2010 Clnical Practice Guidelines on General Anaesthesia for Emergency Situations by the Scandinavian Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine state following: (i) The use of CP cannot be recommended on the basis of scientific evidence (recommendation E, supported by non-randomized, historic controls, case series, uncontrolled studies and expert opinion) (ii) The use of CP is therefore not considered mandatory but can be used on individual judgement (recommendation E). (iii) If facemask ventilation becomes necessary, CP can be recommended because it may reduce the risk of causing inflation of the stomach (recommendation D, supported by non-randomized, contemporaneous controls) The 2005 European Resuscitation Council Guidelines (page 1322, pdf here) puts it this way: - The routine use of cricoid pressure in cardiac arrest is not recommended. - Studies in anaesthetised patients show that cricoid pressure impairs ventilation in many patients, increases peak inspiratory pressures and causes complete obstruction in up to 50% of patients depending on the amount of cricoid pressure (in the range of recommended effective pressure) that is applied. Still though it has to be mentioned that the Difficult Airwas Society (DAS) continues to recommend cricoid pressure for RSI on it's website. The current recommendation though seems to date back to 2004 and the question is mentioned on their website whether any pressure should be applied before loss of consciousness. Also the Association of Anaesthetists in Great Britain and Ireland recommends cricoid pressure in their AAGBI Safety Guidelines of 2009 on pre-hospital anaesthesia. It is also mentioned that 'badly applied cricoid pressure is a cause of a poor view at laryngoscopy. It may need to be adjusted or released to facilitate intubation or ventilation'. While the discussion on this issue in adults will continue the dogma of cricoid pressure might soon fall in paediatric patients as Neuhaus D et al. published a Swiss trial in 2013 where they could show that a controlled rapid sequence induction without cricoid pressure is actually safe. Further research is on its way: Trethrewy E et al. Trials. 2012 Feb 16;13:17. Until then it seems as if we are faced with guidelines mostly still in favour for cricoid pressure and evidence based medicine, which is rather discouraging us of further performing this procedure. It is good practice to constantly question current guidelines and further improve them for the patient's sake. Indeed you have to ask yourself on how far you want to stick to current guidelines for legal reasons or if you change your practice according to emerging evidence. Some of the hospitals I worked at in Switzerland have stopped performing cricoid pressure for RSI some years ago and haven't encountered any worsening in their patient outcomes. Taking into account that most RSI in the ICU resemble emergency intubations out of hospital rather than the controlled environment of a theatre I feel there are good reasons to start re-evaluating and possibly change current guidelines. Other very interesting resources of information can be found here (FOAMed): - lifeinthefastlane.com on cricoid pressure - resus.me on cricoid pressure - Update 02/05/14: Minh Le Cong published a statement of the NAP 4 investigators on his blog website: statement from NAP 4 (on prehospitalmed.com) ... The discussion goes on! |

Search

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed