When the FDA approved dexmedetomidine (DEX) in 1999, intensive care medicine had a novel and highly promising drug at its disposal. Compared to clonidine, dexmedetomidine is an 8 times more selective, central alpha 2 agonist, which binds to all 3 subtypes of the receptor. The properties of this substance were auspicious, among them: sedation, analgesia, neuroprotective effects and a lack of respiratory depression. - Sedation decreases sympathetic activity, aggression and leads to a non-REM-like state, which of all sedatives comes closest to natural sleep. Cognitive functions are maintained, and patients usually remain arousable. - Dexmedetomidine has a particular analgesic effect via modulation in the region of the posterior horn of the spinal cord. This has shown to reduce the use of opiates. - By reducing cerebral catecholamines, dexmedetomidine exerts a neuroprotective effect. - Interestingly, sedation with dexmedetomidine is not associated with significant respiratory depression. These properties pointed to a wide range of applications in the intensive care unit: - Sedation in patients with non-invasive ventilation - Weaning of invasively ventilated patients - Agitated delirium - Treatment of various withdrawal syndromes - Fiberoptic awake intubation in theatre conditions Dexmedetomidine comes with its side effects, though. Most commonly bradycardia and hypotension are observed, making second and third-degree heart block a contraindication. Also, nausea and a dry mouth might be seen. Interestingly, prolonged use might be associated with some extent of discontinuation syndrome similar to clonidine. This involves hypertension, tachycardia, nervousness etc. What Evidence Do We Have So Far? |

|||||||

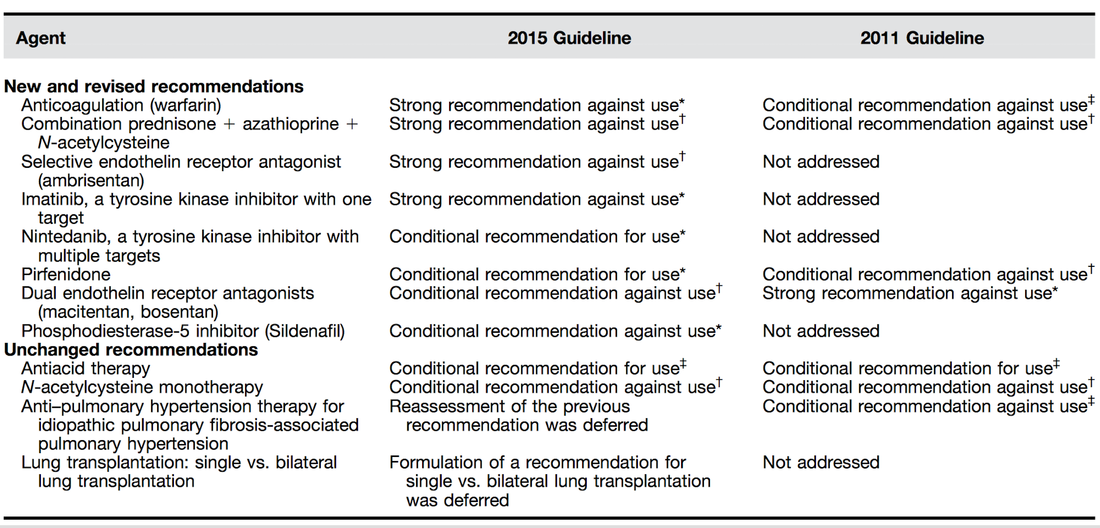

| Acute Exacerbations in Patients with IPF,Kim Respiratory Research 2013, 14:86 | |

| File Size: | 321 kb |

| File Type: | |

To prevent this complication ICU's uniformly have adapted the VAP-bundle, a bunch of measures aiming to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Unfortunately the evidence of the VAP-bundle is not as robust as one might think it is. Here's the evidence of some elements of the VAP bundle:

- Elevation of the head to bed 45° (low evidence)

- Daily sedation interruptions (the impact on reducing VAP has not been shown so far)

- Daily oral chlorhexidine rinses (low evidence)

... it's most likely the combination of measures that is of benefit to the patient... hopefully! But hold on, there is another intervention that finally brings quite some evidence with it!

Active suctioning of the subglottic area, where nasal-oral secretions gather and create a rich culture medium for all sorts of micro-organisms, also aims to reduce the incidence of VAP. In contrast to the classical VAP-bundle the evidence here is strongly in favour for these devices!

In 2005 four registrars in cardiothoracic surgery looked into this topic and summarised their efforts online on Best Evidence Topics, best bets.org. In this blog they review 13 relevant articles on the use of subglottic suctioning and conclude: subglottic suction significantly reduces the incidence of VAP in high risk patients - which means a NNT of 8 if ventilated for more than 3 days. They also mention that this measure is cost effective, despite the more expensive tubes.

In the same year Dezfulian et al. presented a systematic meta-analysis of randomized trials in the American Journal of Medicine. They ended up with 5 studies including 869 patients. They also came to the conclusion that subglottic secretion drainage is effective in preventing VAP in patients expected to be ventilated for more than 72 hours.

In 2011 Hallais et al. looked into the issue of cost-effectiveness with a cost-benefit analysis. Even when assuming the most pessimistic scenario of VAP incidence and costs the replacement of conventional ventilation with continuous subglottic suctioning would still be cost-effective.

In 2011 Muscedere et al. published an 'official' review article in Critical Care Medicine and also ended up with 13 randomised clinical trial, most of them the same 'BestBETs' had already identified 6 years before. It is therefore not surprising to see that they also found a highly significant reduction in VAP. They were also able to demonstrate a reduction in ICU length of stay and duration of mechanical ventilation, although the strength of this association was weakened by heterogeneity of study results.

We finally would like to mention the latest randomised controlled trial on this topic which was published in Critical Care Medicine this January 2015. Damas et al. randomly assigned 352 patients to either receive subglottic suctioning or not. Again sublottic suctioning significantly reduced VAP prevalence and therefore also antibiotic use.

At least we have identified one area in critical care where an impressive pile of evidence supporting the use of subglottic suctioning in long-term intubated patients is present... and even better: cost-effective analyses also come out in great favour for this measure!

Take-home message: Subglottic suctioning does prevent VAP in patients likely to be ventilated more than (48-) 72 hours and should be used in these situations.

Review BestBETs 2005

Dezfulian C et al. Am J Med. 2005 Jan;118(1):11-8

Hallais C. et al. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011 Feb;32(2):131-5

Muscedere J et al. Crit Care Med. 2011 Vol. 39, No. 8

Damas P et al. Crit Care Med. 2015 Jan;43(1):22-30

So far only one prospective, randomised, double-blind trial looked at this question and found a better success rate for linezolid, which was not statistically significant though.

To look at this issue the IMPACT-HAP investigators (Improving Medicine through Pathway Assessment of Critical Therapy in Hospital Acquired Pneumonia) performed a multicenter, retrospective, observational study on 188 patients in 5 hospitals of the U.S.

They found a significantly higher success rate with linezolid compared to vancomycin in the means of improvement or resolution of the signs and symptoms of VAP (primary endpoint). The study did not identify any difference though between linezolid- and vancomycin-treated patients in regards to mortality, development of thrombocytopenia, anaemia, or nephrotoxicity, days of mechanical ventilation or length of stay ion ICU or the hospital itself (secondary outcomes).

Looking into the trial there appear to be several confounding reasons why patients treated with linezolid had better clinical success rate like less severity of sickness in linezolid patients, possible suboptimal vancomycin through levels etc.

Overall there seems no good reasons at this stage to change current guidelines.

Wunderink RG et al. Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia, Clin Infect Dis; 2012, 54:621–629

Peyrani P et al. Crit Care 2014; 18:R118 doi:10.1186/cc13914

48 studies were included to answer the first question, while 37 studies were used to approach question number 2.

In conclusion:

- Light's criteria, pleural fluid cholesterol (<55 mg/dl) and pleural fluid LDH (>200 U/L) levels, and the pleural fluid cholesterol to serum cholesterol ratio (> 0.3) are the best diagnostic indicators for pleural exsudates

- Pneumothorax was the most common complication of thoracocetesis (incidence 6%). Chest tube placement was needed in 2% of all procedures. And most impressive: Ultrasound skin marking by a radiologist or ultrasound-guided thoracocentesis were not associated with a decrease in pneumothorax events.

... would you abandon the ultrasound?

Wilcox et al. JAMA, June 18, 2014, Vol 311, No. 23

So the investigators conclude that a higher level of PEEP and recruitment maneuvres do not protect against postoperative pulmonary complications. They actually advise to use low tidal volumes and very low PEEP for intraoperative ventilation.

The multicenter study is well designed and performed but some questions remain:

Why is PEEP never adjusted to weight?

One striking feature is that we all use tidal volumes according to the patients body weight, but interestingly nobody seems to use this adjustement for weight when it comes to PEEP. Using a PEEP of 12 in a small and slim 50kg patient has a different impact compared to a massively obese patient.

Is 12 cmH2O too high?

A PEEP of 12 can be considered generally high and is not used by most anaesthetists in their daily practice anyway. There was no third arm using intermediate levels of PEEP to answer the question on how these patient might have performed.

Why did other trial find differing conclusions?

The aspect of different levels of PEEP is interesting as previous studies actually were able to show improved outcome with 'protective' mechanical ventilation. The IMPROVE trial in the NEJM from Augut 2013 compared patients for abdominal surgery ventilated with Vt of 10-12ml/kg and 0 cmH2O of PEEP to patients ventilated with Vt of 6-8ml/kg and 6-10 cmH2O of PEEP. In this multicenter, double blind trial with 400 patients improved outcome and reduced health care utilazation were found in the group 'protectively' ventilated.

In june 2013 Anaesthesiology published a prospective randomized small trial with 56 patients undergoing open abdominal surgery for more than 2 hours. This time they compared Vt of 9ml/kg and O PEEP to Vt of 7ml/kg and 10 PEEP. This time 'protective' ventilation with PEEP improved respiratory function but did not affect length of hospital stay.

Taking these fact into account I think we remain with following conclusions:

- The PROVHILO trial is not reason enough to abandon PEEP for anaesthetic ventilation in theatre

- Instead we might have to consider adjusting PEEP to the patients clinical condition (e.g. weight)

- There is no evidence currently to recommend routine recruitment maneuvers in theatre

The Prove Network Investigators, The Lancet, Early Online Publication, 1 June 2014

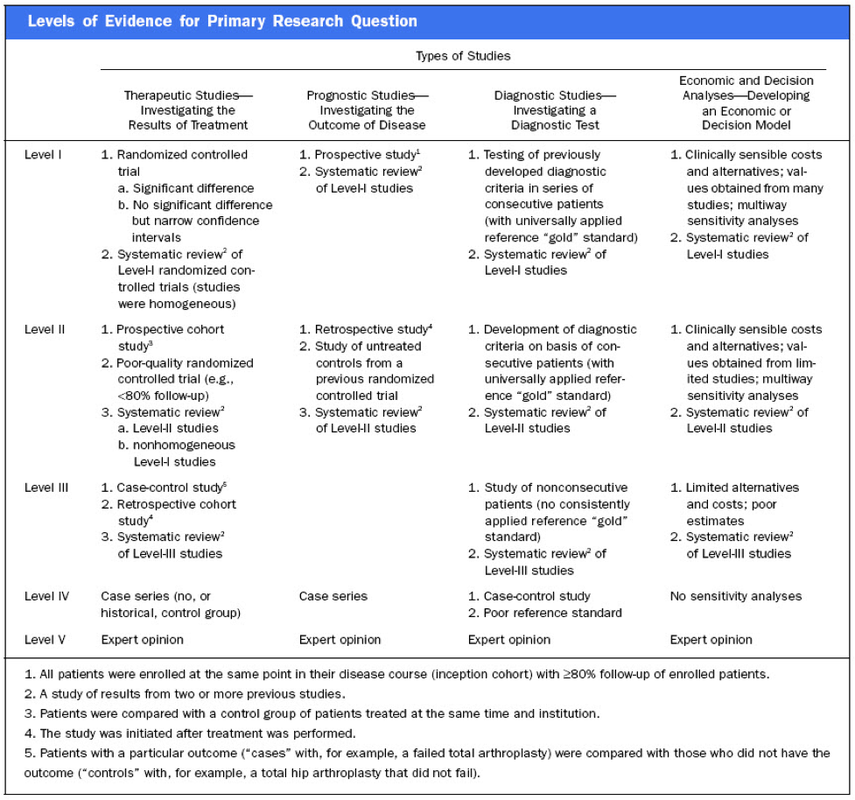

In their publication they state that "there have been no prospective randomized clinical studies performed to prove the clinical hypothesis and the level of evidence to support the use of cricoid pressure is poor (Level 5)". Level 5 corresponds to 'Expert Opinion' (see table below). They also mention that aspiration has occured despite CP, that CP is often poorly performed, that it may hinder bag-valve mask ventilation as well as LMA insertion and that is may worsen laryngoscopy. It's mentioned that "Critically, it has also been shown to potentially obstruct the upper airway and reduce time to desaturation".

'This is nothing new' you might say. Why am I mentioning this? Well, the remarkable thing about this article is the fact that it was published in a Journal that is a joint venture of the British Journal of Anaesthesia BJA and The Royal College of Anaesthetists in collaboration with the Intensive Care Society and Pain Society. Considering the fact that The NAP4 guidelines continue to support its use as part of an RSI and as such, it is still considered a standard of care in the UK and therefore also Ireland, this publication might indicate some change in mind... or not?

The authors summarize: Application of cricoid pressure is advisable — unless it obscures the view at laryngoscopy or interferes with manual ventilation or supraglottic airway device placement.

I personally still would want to know what exactly makes a 'Level 5' medical intervention 'advisable' especially in regards of all the possible problems and complications associated with it.

Wallace et al., Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain, Volume 14(3), June 2014, p 130–135

Read our previous BIJC post: Cricoid Pressure for RSI in the ICU: Time to Let Go? (Updated)

Despite the possibility of some selection bias they conclude that high doses of methylprednisolone are associated with worse outcomes and more frequent adverse effects (like prolonged hospital and ICU length of stay, higher hospital costs, increased length of invasive ventilation, increased need for insulin therapy and higher rate of fungal infections). Mortality itself did not significantly differ.

It is remarkable to note that in this study doses below 240mg of methylprednisolone are considered low-dose. This is equivalent to 300mg of prednisolone and is relatively high for exacerbations of COPD. As we mentioned in a post in November 2013 the REDUCE trial in JAMA compared 5 days to 14 days of steroids in exacerbated COPD. The dosage used there was 40mg of prednisone. The results showed that a 5-day treatment was non-inferior to a 14-day treatment with regard to re-exacerbation within 6 months but significantly reduced glucocorticoid exposure.

In summary it seems to be advisable to use lower doses and short treatment periods in acute exacerbated COPD.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014 May 1;189(9):1052-64

Over the last couple of years though this manoeuvre has been seriously questioned as scientific evidence is lacking and there are concerns that cricoid pressure might actually be potentially harmful.

A lot has been written on this topic so far and some great reviews can be found easily on the internet thanks to the concept of Open Free Access Meducation (FOAMed, see below). Still I would like to add some thoughts on to this discussion and maybe mention one or two more interesting facts.

Cricoid pressure was actually first described by Sellick in the Lancet in 1961 as a preliminary report and basically represented an un-controlled case study in which no or only insufficient information on the studies patient population was provided. There was no standardisation of the force for cricoid pressure as of the medications used for induction. There was also no information on the quality of laryngoscopy and intubation. Steinmann and Priebe (abstract in english) have exactly analysed this publication and found some relevant methodological shortcomings. It is therefore remarkable that this publication led to an anaesthetic dogma practised all over the world.

As mentioned in the European Resuscitation Council Guidelines of 2005, studies in anaesthetised patients show that cricoid pressure impairs ventilation in many patients, increases peak inspiratory pressures and causes complete obstruction in up to 50% of patients depending on the amount of pressure applied (Petito, Lawes, Hartsilver, Allman, Hocking, Mac, Ho, Shorten).

The incidence of a difficult intubation is significantly higher in preclinical emergency situations than in an elective theatre environment (Timmermann A et al. Resuscitation 2007;70(2):179-185). It is therefore possible, that cricoid pressure itself actually is one of the reasons why unexperienced emergency physicians experience additional difficulties when intubating 'in the field'.

One concern often mentioned is the fear that non-adherence to current guidelines by not applying cricoid pressure might have adverse legal implications. But what do current guidelines actually say? Priebe et al. partially looked at this in 2012. Several guidelines indeed still recommend cricoid pressure, sometimes even with less force in the awake patient. But some guidelines have started to implement current evidence.

The 2010 Clnical Practice Guidelines on General Anaesthesia for Emergency Situations by the Scandinavian Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine state following:

(i) The use of CP cannot be recommended on the basis of scientific evidence (recommendation E, supported by non-randomized, historic controls, case series, uncontrolled studies and expert opinion)

(ii) The use of CP is therefore not considered mandatory but can be used on individual judgement (recommendation E).

(iii) If facemask ventilation becomes necessary, CP can be recommended because it may reduce the risk of causing inflation of the stomach (recommendation D, supported by non-randomized, contemporaneous controls)

The 2005 European Resuscitation Council Guidelines (page 1322, pdf here) puts it this way:

- The routine use of cricoid pressure in cardiac arrest is not recommended.

- Studies in anaesthetised patients show that cricoid pressure impairs ventilation in many patients, increases peak inspiratory pressures and causes complete obstruction in up to 50% of patients depending on the amount of cricoid pressure (in the range of recommended effective pressure) that is applied.

Still though it has to be mentioned that the Difficult Airwas Society (DAS) continues to recommend cricoid pressure for RSI on it's website. The current recommendation though seems to date back to 2004 and the question is mentioned on their website whether any pressure should be applied before loss of consciousness.

Also the Association of Anaesthetists in Great Britain and Ireland recommends cricoid pressure in their AAGBI Safety Guidelines of 2009 on pre-hospital anaesthesia. It is also mentioned that 'badly applied cricoid pressure is a cause of a poor view at laryngoscopy. It may need to be adjusted or released to facilitate intubation or ventilation'.

While the discussion on this issue in adults will continue the dogma of cricoid pressure might soon fall in paediatric patients as Neuhaus D et al. published a Swiss trial in 2013 where they could show that a controlled rapid sequence induction without cricoid pressure is actually safe.

Further research is on its way: Trethrewy E et al. Trials. 2012 Feb 16;13:17. Until then it seems as if we are faced with guidelines mostly still in favour for cricoid pressure and evidence based medicine, which is rather discouraging us of further performing this procedure. It is good practice to constantly question current guidelines and further improve them for the patient's sake. Indeed you have to ask yourself on how far you want to stick to current guidelines for legal reasons or if you change your practice according to emerging evidence.

Some of the hospitals I worked at in Switzerland have stopped performing cricoid pressure for RSI some years ago and haven't encountered any worsening in their patient outcomes. Taking into account that most RSI in the ICU resemble emergency intubations out of hospital rather than the controlled environment of a theatre I feel there are good reasons to start re-evaluating and possibly change current guidelines.

Other very interesting resources of information can be found here (FOAMed):

- lifeinthefastlane.com on cricoid pressure

- resus.me on cricoid pressure

- Update 02/05/14: Minh Le Cong published a statement of the NAP 4 investigators on his blog website: statement from NAP 4 (on prehospitalmed.com)

... The discussion goes on!

Tischenkel BR et al. have now looked at this topic in a retrospective cohort study of two hospitals in the state of New York. In this paper, published in the Journal of Intensive Care Medicine this month, they looked at a total of 2240 patients which were extubated in intensive care units over the period of almost 2 years. As a result they could show that nighttime extubations did not have a higher likelihood of reintubation, length of stay or mortality compared to those during the day. They conclude that patients should be extubated as soon as they meet parameters in order to potentially decrease complications of mechanical ventilation. These data, they say, do not support delaying extubations until daytime.

I fully agree... as long as there is somebody in the unit able to deal with potentially deleterious complications!

Tischenkel BR et al. J Intensive Care Med April 24, 2014

In June 2013 Guerin et al. published the PROSEVA trial which indeed showed some amazing results. It is the 5th biggest trial of it's kind and finally was able to actually now show a dramatic reduction in mortality: the 28 day mortality was 32.8% in the supine group (229 patients), compared to only 16% in the prone group (237 patients). This benefit in outcome persisted also after 90 days... a miracle?

Most probably these results reflect the very strict adherence to the guidelines of ARDSnet in regards of paralysation and use of very low tidal volumes. One thing that has to be mentioned is the high number of patients with ARDS which have excluded from the trial for several reasons.

So should we now follow this study and prone more aggressively?

One answer might be the just recently published meta-analysis by Lee at al. in Critical Care Medicine. This paper looked at a total of 11 randomised controlled trials and therefore takes all recent publications into account. The authors come to the conclusion that prone positioning indeed does reduce mortality significantly and were marked in the subgroup where the duration of prone positioning was more than 10 hours. This is the first time somebody actually comments on the length of prone positioning in terms of benefit for the patient.

As always though there are also adverse effects of this therapy as prone positioning was significantly associated with pressure sores and maybe most importantly major airway problems.

Overall, the concept of prone positioning in severe ARDS seems to be well established and should be implemented in the clinical procedures of every intensive care unit. This is particularly true for regions where quick access to extra corporal CO2 removal or oxygenation devices is difficult.

Guerin C et al. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jun 6;368(23):2159-68.

Lee JM et al. Crit Care Med. 2014 May;42(5):1252-62.

Ferguson et al. Intensive Care Med. 2012 Oct;38(10):1573-82.

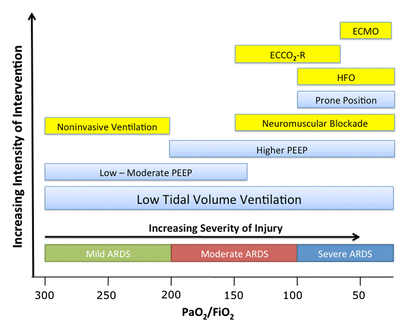

A very nice and quick overview on treatment options for ARDS was presented by Ferguson et al. in Intensive Care Medicine 2012:

Quint et al. have looked into this topic by performing a retrospective study including 1063 COPD patients, who experienced their first AMI. 55.1% of these patients were never prescribed a beta blocker throughout the study period, 23% were on beta blockers before and 21.9% were prescribed a beta blocker during their hospital admission for AMI.

Patients started on beta blocker during their hospital admission showed substantial survival benefits compared to patients who were not prescribed any beta blockers. Patients taking beta blockers before their first myocardial infarction also showed a substantial survival benefit!

Taking into the account these results and the increasing evidence that beta blocker are actually safe in COPD patients suggests that beta blockers should be used more widely in patients at risk for AMI.

At least we should not be too worried to prescribe them.

Quint J K et al. BMJ 2013;347:f6650

Dransfield M T et al. Torax 2008;63:301-305

Results showed that a 5-day treatment was non-inferior to a 14-day treatment with regard to re-exacerbation within 6 months but significantly reduced glucocorticoid exposure. As so often: Less is more!

Leuppi JD, et al. JAMA. 2013 Jun 5;309(21):2223-31

Search

Translate

Select your language above. Beware: Google Translate is often imprecise and might result in incorrect phrases!

Categories

All

Airway

Cardiovascular

Controversies

Endocrinology

Fluids

For A Smile ; )

Guidelines

Infections

Meducation

Neurology

Nutrition

Pharmacology

Procedures

Radiology

Renal

Respiratory

Resuscitation

SARS CoV 2

SARS-CoV-2

Sedation

Sepsis

Transfusion

Archives

January 2021

September 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

July 2019

May 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

January 2018

October 2017

August 2017

June 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

October 2016

July 2016

June 2016

April 2016

February 2016

December 2015

October 2015

September 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

January 2015

December 2014

November 2014

October 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

June 2014

May 2014

April 2014

March 2014

February 2014

January 2014

December 2013

November 2013

Author

Timothy Aebi

RSS Feed

RSS Feed