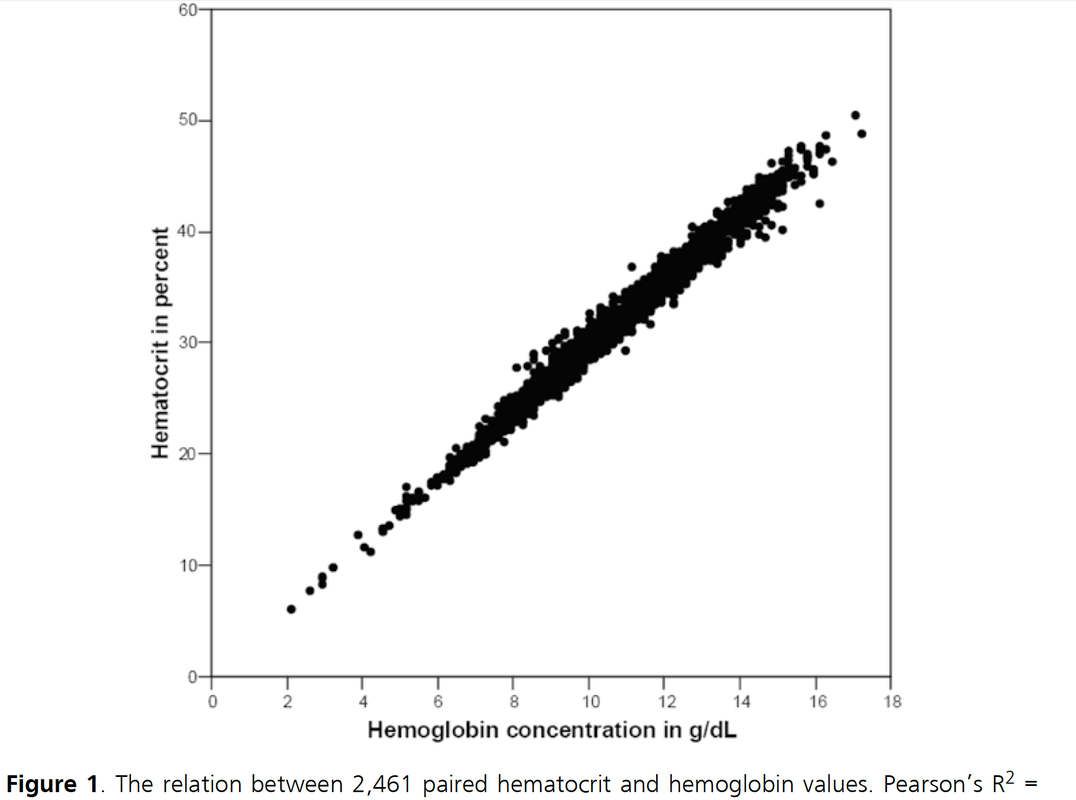

It starts in medical school, regularly appears in your medical training, sneaks around nursing schools and is an impetus for discussions in the ICU: The great myths about Hemoglobin (Hb) and Hematocrit (Hct). These two haematological lab-parameters are part of our daily life at work and are mostly measured together... as a package. Some clinicians look at haemoglobin levels, others prefer hematocrit levels... but then there is always someone making a great deal of differentiating between the two parameters and making all sort of diagnostic conclusions. 'Hct is better to determine dilution of the patient' or 'Acute blood loss is better determined by Hb than Hct'... and so on. So here's the question: What actually is the difference between Hb and Hct? Do we need to measure both in clinical practice? What's the difference? Hemoglobin levels are mostly measured by automated machines designed to perform different tests in blood. Within the machine, the red blood cells are broken down to get the haemoglobin into a solution. The concentration of haemoglobin is then measured by spectrophotometry using the methemoglobin cyanide method. Hematocrit levels in contrast are actually calculated by an automated analyzer... It is actually not measured directly! The analyser multiplies the red blood cell count by their mean corpuscular volume. What is Fact? There simply is NO difference between Hemoglobin and Hematocrit by means of clinical information!

Conclusion

Once and for all! Nijboer J et al. J Trauma. 2007;62(5):1310-2.

Beverley Hunt at al. have just published an excellent practical guideline for the haematological management of major haemorrhage which also serves a a great educational review on this topic... an excellent piece of work! The authors look at this topic point for point and review current literature in an easy to understand sort of manor. They define major blood loss when it leads to a heart rte of >110/Min or a systolic blood pressure of less than 90mmHg, or simply said: when bleeding becomes haemodynamic relevant. In general it is recommended to have a major haemorrhage protocol at hand (1D) and all staff should be trained to recognise major blood loss early (1D). Here's a summary of the recommendations made by the British Committee for Standards in Haematology (BCSH): In Major Haemorrhage.... Red Blood Cells RBC - Hospitals must be prepared to provide emergency Group 0 red cells and group specific red cells (1C) - Patients must have correctly labelled samples taken before administration of emergency Group 0 blood (1C) - There is NO indication to request 'fresh' or 'young' red cells (under 7d of storage, 2B) - Note: The optimum target haemoglobin concentration (Hb) in this clinical setting in general is NOT established. Current literature shows a tendency towards restriction towards 70-90g/L, but the BCSH makes no recommendations therefore (see blow) Cell Salvage (e.g. cell saver) - 24h access to cell salvage should be available in cardiac, obstetric, trauma and vascular centres (2b) Haemostatic Monitoring - Use haemostatic tests regularly during haemorrhage, every 30-60min, depending on severity of blood loss (1C) - Measure platelet count, PT, aPTT (1C) - Note: The BCSG does not recommend TEG and ROTEM at this stage Fresh Frozen Plasma FFP - Use FFP in a 1:2 ratio with RBC initially (2C) - Once bleeding is under control administer FFP when PT and/or aPTT is >1.5 times normal (recommended dose 15-20ml/kg, 2C) - The use of FFP should not delay fibrinogen supplementation if necessary (2C) Fibrinogen - Supplement fibrinogen when levels fall below 1.5g/L Prothrombin Complex Concentrates PCC - Do not use PCC Platelets - Keep the platelet count >50 x 10^9/L (1B) - If bleeding persists give platelets if count falls below 100 x 10^9/L (2C) Tranexamic Acid TA - Give tranexamic acid as soon as possible to patients with, or at risk of major haemorrhage (Recommended dose: 1g IV over 10min, followed by 1g IV over 8h, 1A) - Note: TA has no known adverse effects - Note: Aprotinin is not recommended Recombinant Activated Factor VIIa (Novo Seven) - Do not use Specific Clinical Situations Obstetrics - Fibrinogen levels increase during pregnancy to 4-6g/L - In major obstetric haemorrhage fibrinogen should be given when levels are <2.0g/L (1B) GI-Bleed - Use restrictive strategy for RBC transfusion is recommended in most patients (1A) Trauma - Transfuse adult trauma patients empirically with a 1:1 ratio of FFP : RBC (1B) - Consider early use of platelets (1B) - Give tranexamic acid as soon as possible (Dose 1g over 10min and then 1g over 8h, 1A) Prevention of Bleeding in High-Risk Surgery - Use tranexamic acid (Dose 1g over 10min and then 1g over 8h, 1B) Hunt B et al. British J Haemat, July 6 2015 Read more HERE: Great Review on Transfusion, Thrombosis and Bleeding Management Restricitve Transfusion Threshold in Sepsis, the TRISS Trial Transfusion: Harmful for Patients Undergoing PCI?  'Anaesthesia', the Journal of the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland have published an Open Access Supplement on various aspects of Transfusion, Thrombosis and Bleeding Management. This is an excellent opportunity to update your knowledge in this field and actually compulsory for anyone involved actively in critical care. The supplement consists of multiple review articles which are kept nice and short and are perfect for reading in between... In Conclusion: Reading highly recommended! On following website you can find a list of all articles including links to the full text: Anaesthesia, Vol. 70, Issue Supplement s1, January 2015: Transfusion, Thrombosis and Bleeding Management  Several studies in the past have looked into the topic of red blood cell (RBC) transfusions in the ICU and each one of them supports a rather restrictive approach in the ICU. Still though various guidelines around the world vary due to the lack of evidence (see below). This october the New England Journal of Medicine (unnoticeably and slowly transforming into a critical care journal ;) published a large multi-centered, partially blinded trial that randomised septic patients in intensive care units to receive RBC at a threshold of 70g/L or 90g/L. The primary outcome was mortality after 90 days. A total of 998 patients finally underwent randomisation and as a result there was no significant difference in mortality after 90 days. Also there were no statistically significant differences in all secondary endpoints like use of life supporting measures, ischemic events, and severe adverse reactions. This trial adds up to a list of studies showing that a liberal transfusion strategy is not beneficial for patients in critical care. This seems to be especially true for patients with sepsis. And not to forget: a considerable amount of packed RBC can be saved this way. A higher transfusion threshold of 90g/L in patients with sepsis is non-superior to a lower threshold of 70g/L. Get an insight into this topic yourself, here's the 'must read's about transfusions: The TRICC trial The CRIT study Sherwood M et al. JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;Vol 311, No.8 The FOCUS trial A short educational overview can be found here: http://lifeinthefastlane.com/education/ccc/blood-transfusion-in-icu/ Clinical Practice Guidelines from the AABB 2012: Ann Inten Med. 2012;157:49-58 Clinical Practice Guidelines 2009: Red blood cell transfusion in adult trauma and critical care, Crit Care Med 2009  The transfusion of red blood cells in the ICU remains a hot topic not only since the CRIT study and TRICC trial. It has been associated with complications and worse outcome. Unfortunately anemia and bleeding are common problems in critical care and therefore transfusions remain an important tool in the treatment in these patients, especially as we know that anemia itself is harmful. The question still remains when and in which situations RBC transfusions are indicated and helpful, especially in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD). The TRICC trial in the NEJM in 1999 concluded: ‘A restrictive strategy of red-cell transfusion is at least as effective as and possibly superior to a liberal transfusion strategy in critically ill patients, with the possible exception of patients with acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina’. The clinical practice guidelines from the AABB in 2012 noted that they can not recommend for or against a liberal or restrictive transfusion threshold for stable patients with acute coronary syndrome Now JAMA addresses the issue of transfusion in patients with CHD undergoing percutaneous intervention (PCI). In this retrospective cohort study they looked at 2’258’711 patients (now that’s a number) in 1431 hospitals who underwent PCI in a period of almost 4 years. Despite a considerable variation on blood transfusions practices among these US hospitals, the receipt of transfusion was associated with increased risk of in-hospital cardiac events (myocardial infarction, stroke and hospital death). ... another puzzle piece towards restriction? Sherwood M et al. JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;Vol 311, No.8 Look up here: The TRICC trial and the CRIT study (the ‘need to know’s) A short educational overview can be found here: http://lifeinthefastlane.com/education/ccc/blood-transfusion-in-icu/ Clinical Practice Guidelines from the AABB 2012: Ann Inten Med. 2012;157:49-58 Clinical Practice Guidelines 2009: Red blood cell transfusion in adult trauma and critical care, Crit Care Med 2009 |

Search

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed