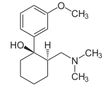

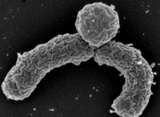

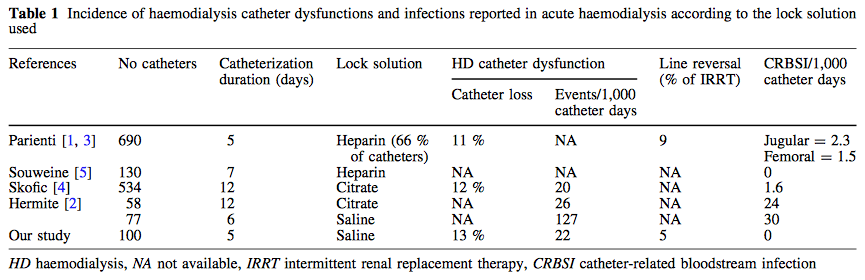

Many patients admitted to the emergency department (ED) suffer of nausea and vomiting - and many doctors treat this with antiemetics like metoclopramide or ondansetron. Treating nausea is tricky and of course we all try to do our best to comfort patients as good as possible. But are you really sure giving an antiemetic in the ED actually improves symptoms? Unfortunately results coming in on this topic do not look very promising. 3 publications looked at exactly this setting and although their number of patients isn't overwhelming the results are rather discouraging. Egerton-Warburton and colleagues performed a RCDT and looked a total 258 patients who got either metoclopramide, ondansetron or normal saline as a treatment for nausea in the ED. They basically found no differences in reduction of nausea severity. Back in 2006 Braude et al. already stated in a RCDT including 97 patients that metoclopramide and prochlorperazine were not more effective than saline placebo as an antiemetics in the ED. Only droperidol was found to be more effective than metoclopramide or prochlorperazine but caused more extrapyramidal symptoms. And in 2011 Barrett and colleagues published a study with 163 patients where they compared metoclopramide, ondansetron, promethazine and saline placebo in the ED. Same again: no evidence was found that ondansetron is superior to metoclopramide and promethazine in reducing nausea in ED adults. Even if the number of patients is not that big... it's three trials so far and they all don't really support the use of antiemetics in the emergency department. It is interesting to note that these drugs have been proven to be effective in the setting of chemotherapy and in anaesthetics, but the setting in the ED seems to differ. At least most patients experienced some relief over time... most probably to treatment of the cause itself! Egerton-Warburton et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:526-532 OPEN ACCESS Braude, D et al. Am J Emerg Med. 2006; 24: 177–182 Barrett et al. Am J Emerg Med. 2011; 29: 247–255  Developed in the early 70'ies tramadol has become a very popular drug for pain relief for various reasons. Among others it is often said that tramadol is safe to use and has non-addictive properties, making this an ideal opioid to use for in and out of hospital. The facts though point in the opposite direction. In JAMA Internal Medicine Fournier et al. have just published a case control analysis to look at the fact that tramadol before has been associated with the occurrence of significant hypoglycemia. Their cohort included a total of 334'034 patients whereas each case of hospitalization for hypoglycemia was matched with up to 10 controls on age, sex, and duration of follow-up. Basically they compared similar patients which were either started on tramadol or codeine for pain treatment. They were able to show that compared with codeine, tramadol use was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for hypoglycemia, particularly in the first 30 days of use. It has to be noted though, that the overall incidence is low with 7 per 10'000 per annum. In the same issue's commentary Nelson and Juurlink take the opportunity to point out some other remarkable problems associated with Tramadol, again showing us that things are not a simple as we think they are. - Tramadol itself has only a low affinity to opioid receptors and mainly works over one of its metabolites: O-Desmethyltramadol (M1), which then binds to µ opioid receptors - The expression of the enzyme that metabolites tramadol to M1 is extremely variable, thus: giving a certain dose of tramadol leaves you with an unknown dose of acting opioid! - Despite suggestions to the contrary, tramadol does pose a risk for addiction - And there are increasing reports of deaths involving this drug - Other documented adverse effects are: serotonin syndrome and seizures Conclusion: Tramadol remains a non-ideal drug in the setting of an ICU. Fournier et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):186-193. Nelson and Juurlink JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):194-195.  Again we have picked a review article looking at fluid resuscitation in the ICU. This article by Lira et al. in the Annals of Intensive Care looks at all the new literature available in regards of fluid therapy during resuscitation. Also review current recommendations and recent clinical evidence. This results in an excellent systematic review that leaves us with following conclusions: - Currently no indications exist for the routine use of colloids over crystalloids - In regards of current evidence (including the Albios trial), the cost and limited shelf time the use of albumin as a resuscitation fluid is not recommended - The use of hydroxy-ethyl-starch (HES) during resuscitation should be avoided - In light of the lack of evidence, and the theoretical potential for adverse effect, the suggestion is to avoid gelatine or dextran - The use of 0.9% normal saline is associated with the development of hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis and increased risk of AKI in susceptible patients. Therefore balanced crystalloid solutions should be considered/ preferred - Current literature supports the use of balanced crystalloid solutions (e.g. Hartmann's solution, Ringer's lactate) whenever possible This makes things quite simple actually... but of course opinions differ! Lira and Pinsky, Annals of Intensive Care Dec 2014, 4:38 OPEN ACCESS Read here: The Albios trial  Just recently in 2014 the WHO has requested to develop a draft global action plan to combat emergent antimicrobial resistance (AMR). AMR is present in all parts of the world, new resistance mechanisms emerge and spread globally. And most importantly: Patients with infections by drug-resistant bacteria are generally at risk of worse clinical outcome and death. On the background of this the recent publication in Nature by Ling et al. is remarkable as it might offer the key to a new antimicrobial weapon in the near future. Teixobactin is the name of a macrocylic peptide representing a new class of antibiotics. It appears to be potent bactericidal agent against a broad panel of bacterial pathogens, especially gram-positive bacteria including MRSA, enterococci and VRE as well as M. tuberculosis, C. difficile and Anthrax. Teixobactin inhibits cell wall synthesis and most remarkably showed no development of resistance so far. Teixobactin is produced by E. terrae, a microorganism discovered in the soil of a grassy field in Maine. As mentioned in the article, these 'uncultured' bacteria make up approximately 99% of all species in external environments, and are an untapped source of new antibiotics. An interesting article, especially if you want to see what's going on outside the hospital! Ling LL et al. Nature 2015; doi:10.1038/nature14098 Enteral Naloxon Safely Prevents Opioid Induced Constipation... Now also Confirmed in the NEJM26/9/2014

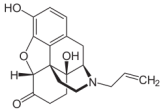

It's not really the biggest news, but it's in the NEJM and it lines up with several publications looking at preventing opioid induced constipation with enteral naloxone. The article is remarkable in that sort of way as it represents a quite big double blinded study, while many publications before had a rather descriptive character. It has been shown before, that enteral naloxone helps reduce constipation when administered in conjunction with oxycodone. Interestingly enteral administration of naloxone blocks opioid action at the intestinal receptor level, but has a low systemic bioavailability due to marked hepatic first pass metabolism. In this study the investigators used naloxegol which is a PEGylated form of naloxone. This means that polyethylene glycol (PEG) polymer chains were covalently attached to the naloxone molecule. Chey WD et al. now basically present 2 double blinded studies including 625 patients in one and 700 patients in the other. Outpatients with non-cancer pain who were already getting opioids and experienced constipation were randomly assigned to receive either enteral naloxone (12.5mg or 25mg) or placebo. Primary endpoint was clinical response after twelve weeks defined as more than 3 bowel motions per week or an increase in bowel motions. Result: Enteral naloxone significantly reduced time to to the first post dose spontaneous bowel motion and increased the frequency of bowel motions. It is important to note that enteral naloxone did not reduce opioid mediated analgesia. Enteral naloxone should be considered in prevention or treatment of opioid induced constipation, also in the ICU. Chey WD et al. N Engl J Med. (2014) Webster et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014 Oct;40(7):771-9 This might also be of interest: Meissner et al. Crit Care Med. 2003 Mar;31(3):776-80, Enteral naloxone reduces gastric tube reflux and frequency of pneumonia in critical care patients during opioid analgesia.  Anaemia is a very common finding in critically ill patients and the idea to Supplement IV iron in these patients sounds tempting. Intravenous iron preparations are licensed for patients with iron deficiency anaemia when oral iron preparations are ineffective or contraindicated. The question is whether IV iron is also helpful in the critically ill. Pieracci et al. have looked at this question more precisely and published their results in Critical Care Medicine. In their multicentre, randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled study they enrolled a total of 150 critically ill trauma patients in which baseline iron markers were consistent with functional iron deficiency anaemia. They randomized patients to either receive iron sucrose 100mg IV or placebo three times a weeks for up to 2 weeks. They found that treatment with IV iron increased ferritin concentration significantly but had no effect on transferrin saturation, iron-deficient erythropoiesis, haemoglobin concentration or packed RBC transfusion requirement. In conclusion: IV iron supplementation in anaemic, critically ill trauma patients cannot be recommended. Pieracci F et al. Crit Care Med, September 2014 - Volume 42 - Issue 9 - p 2048–2057  After a pause and thanks to Kuno's attentiveness following article found it's way to our website: Although not being very popular in the world of intensive care Digoxin remained a component of our armament and was continued to be used for patients with atrial fibrillation. After its long era in medicine findings of the TREAT-AF are now about to bring this to a possible end. Turakhia et al. looked at over 122'000 patients with newly diagnosed, non valvular AF in the U.S. between 2004 to 2008. They specifically looked at the use of Digoxin and the occurrence of death. Residual confounding was assessed by sensitivity analysis. They found a cumulative higher mortality rate for patients treated with Digoxin, which persisted after multivariate adjustment, propensity matching and adjustment for drug adherence. The findings of this study are impressive and even led Harlan Krumholz, editor-in-chief of NEJM Journal Watch Cardiology, to the statement: 'It's time to pause on Digoxin until studies can assure that it's providing a net benefit to these patients'. Turakhia et al. JACC, Aug 19 2014; Volume 64, Issue 7 NEJM Journal Watch Cardiology  Ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) is a problem in ICU around the world and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is the most common multi-drug resistant pathogen to deal with. Current guidelines mostly recommend vancomycin as a first line treatment and linezolid as an alternative, considering both drugs at a similar level of efficacy. The question remained whether linezolid might be superior to vancomycin. So far only one prospective, randomised, double-blind trial looked at this question and found a better success rate for linezolid, which was not statistically significant though. To look at this issue the IMPACT-HAP investigators (Improving Medicine through Pathway Assessment of Critical Therapy in Hospital Acquired Pneumonia) performed a multicenter, retrospective, observational study on 188 patients in 5 hospitals of the U.S. They found a significantly higher success rate with linezolid compared to vancomycin in the means of improvement or resolution of the signs and symptoms of VAP (primary endpoint). The study did not identify any difference though between linezolid- and vancomycin-treated patients in regards to mortality, development of thrombocytopenia, anaemia, or nephrotoxicity, days of mechanical ventilation or length of stay ion ICU or the hospital itself (secondary outcomes). Looking into the trial there appear to be several confounding reasons why patients treated with linezolid had better clinical success rate like less severity of sickness in linezolid patients, possible suboptimal vancomycin through levels etc. Overall there seems no good reasons at this stage to change current guidelines. Wunderink RG et al. Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia, Clin Infect Dis; 2012, 54:621–629 Peyrani P et al. Crit Care 2014; 18:R118 doi:10.1186/cc13914  Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and antibiotic induced Clostridium difficile diarrhoea are a constant problem in the ICU, especially in the elderly patient. There is still some debate going on about prescribing lactobacilli or bifidobacteria for the prevention and treatment of this sort of complication. In this Lancet multi centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pragmatic, efficacy trial this was studied on almost 3000 patients: 10.8% diarrhoea with lactobacilli or bifidobacteria versus 10.4% diarrhoea in the placebo group. No difference! One drug less to prescribe... Lancet 2013 Oct 12;382(9900):1249-57  In a letter to the editor of Intensive Care Medicine Soubirou et al. present the result of a study looking at the efficacy and safety of saline lock solution in maintaining short term hemodialysis catheters patency in ICU. This prospective cohort study looked at 100 double lumen hemodialysis catheters inserted in 75 patients managed with intermitted hemodialysis. At the end of each session the lumens were flushed with normal saline only. The investigators found no difference to 5 other studies using heparin or citrate. Conclusion: Heparin is not necessary in this setting, citrate is an alternative, but saline seems just as good. Soubirou JF et al. Intensive Care Med. 2014 June  This months issue of the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine presents a retrospective cohort study comparing patients with acute exacerbation of COPD receiving either lower-dose methylprednisolone (<240mg/d) or high-dose methylprednisolone (>240mg/d). They looked at 17'239 patients. The primary outcome was mortality. Despite the possibility of some selection bias they conclude that high doses of methylprednisolone are associated with worse outcomes and more frequent adverse effects (like prolonged hospital and ICU length of stay, higher hospital costs, increased length of invasive ventilation, increased need for insulin therapy and higher rate of fungal infections). Mortality itself did not significantly differ. It is remarkable to note that in this study doses below 240mg of methylprednisolone are considered low-dose. This is equivalent to 300mg of prednisolone and is relatively high for exacerbations of COPD. As we mentioned in a post in November 2013 the REDUCE trial in JAMA compared 5 days to 14 days of steroids in exacerbated COPD. The dosage used there was 40mg of prednisone. The results showed that a 5-day treatment was non-inferior to a 14-day treatment with regard to re-exacerbation within 6 months but significantly reduced glucocorticoid exposure. In summary it seems to be advisable to use lower doses and short treatment periods in acute exacerbated COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014 May 1;189(9):1052-64 Simply Great and Helpful: Normogram for Calculating the Maximum Dose of Local Anaesthetics20/5/2014

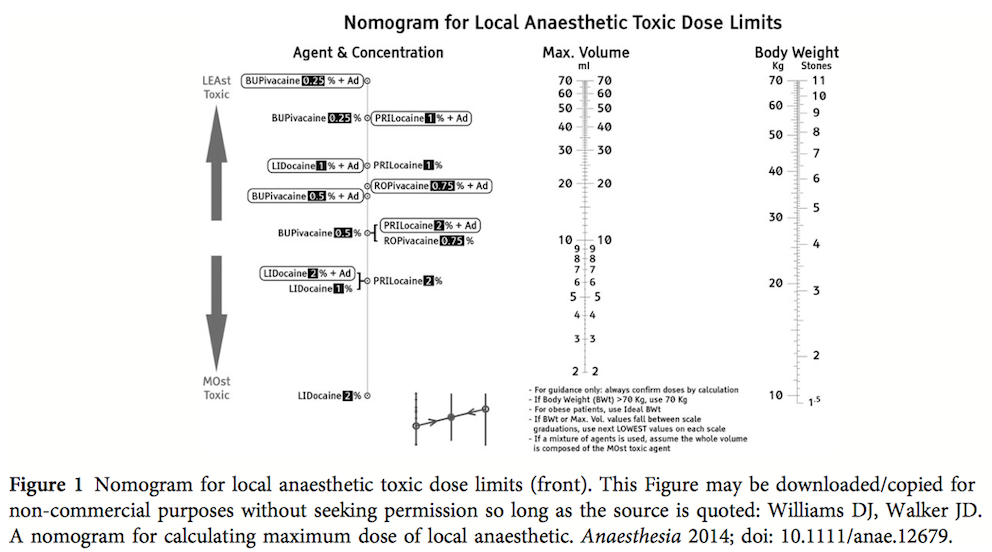

While many medical articles conclude 'more research is needed...', or further study is required' here comes a straight forward article that gives you a simple, but very helpful tool for your daily work. In this month's Anaesthesia Williams and Walker present a normogram for calculation of the maximum safe volume (ml) of local anaesthetic to a clinical acceptable degree of accuracy. Indeed this normogram allows you to find out the various doses within a few seconds. In their article they looked at 14 commonly used local anaesthetics and provide some further background information. The normogram only works with body weights up to 70kg, but they recommend to use the ideal body weight for obese patients. An article worth reading (open access!) and a normogram worth using! Williams DJ et al. Anaesthesia. doi: 10.1111/anae.12679  The amino-acid glutamin seems to play an important role in the critically ill patient by inducing cellular protection pathways, modulation of the inflammatory response and the prevention or organ injury. Glutamine depletion on ICU admission has been linked with increased mortality and clinical trials form the last 20 years demonstrated reduced mortality, infectious complications and ICU/hospital length of stay when giving glutamine. This is one of the reasons ICU's give glutamine when total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is required. ...sounds like all ICU patients should get glutamine! In April 2013 the NEJM published a randomised trial of glutamine and antioxidants in critically ill patient by Heyland et al. Against their expectations they found a trend towards increased mortality at 28 days among patients who received early glutamine intravenously and enterally as compared to those who did not. Actually, the early provision of glutamine did not improve clinical outcome and glutamine was associated with an increase in mortality among critically ill patients with multi-organ failure. ... so should we stop giving glutamine? In April 2014 now Heyland and his co-authors (the same guy from the NEJM paper) published a systematic review in Critical Care. In this paper they looked at 26 publications on parenteral glutamine supplementation in the ICU and could actually show that in conjunction with nutrition support glutamine was associated with a significant reduction in hospital mortality and hospital length of stay. They stated that parenteral glutamine supplementation as a component of nutrition support should continue to be considered to improve outcomes in critically ill patient. ... that all seems confusing and contradicting! Actually all these papers aren't conflicting at all. They offer a differentiated insight into the usage of glutamine... the answer lies in the written details of the study settings. Heylands publication in the NEJM presents a quite different setting compared to most of the previous studies where glutamine was found to be rather beneficial. In the NEJM's publication patients received the highest dose of glutamine (more than in other studies before) which was given intravenously and enterally. This study specifically included critically ill patients with multi-organ failure, most of them in shock. In most previous studies this was an exclusion criteria. Also treatment with glutamine was initiated within 24h after admission to ICU, whereas other studies gave glutamine later in the course of disease together with TPN. And finally all these patients received enteral nutrition, while previous studies mostly focused on parenteral nutrition (TPN). And finally, Heyland (again) just now published a post hoc analysis of the NEJM publication in the Journal of Parenteral & Enteral Nutrition (JPEN) showing that early administration of high-dose glutamine separately from artificial nutrition had the greatest potential to be harmful in patients with multi-organ failure that included renal dysfunction. For these reasons Heyland came to the conclusion that early administration of glutamine in critically ill patients with multi-organ failure was harmful. At the same time it seems beneficial when given after resolution of shock especially in the conjunction with TPN. Summarized: - Early administration of high-dose glutamine in critically ill patients with multi-organ failure may be harmful, especially in conjunction with renal dysfunction - Supplemental glutamine (predominantly as a component of TPN) may improve clinical income when given to appropriate patients and after resolution of multi-organ failure and shock - Supplemental glutamine should not be given in high dose (>0.5 g/kg/d) Wischmeyer PE, Critical Care 2014,18;R76 Qi-Hong C, Critical Care 2014,18;R8 Heyland D, N Engl J Med 2013;368:1489-97 Heyland D, J Parenter Enteral Nutr, May 5 2014 One of the Big Mysteries Solved: How to Correctly Prescribe the Duration of Antibiotic Treatments2/5/2014

Just this week the World Health Organisation WHO has issued a warning that resistance of organisms to antibiotics will become one of the biggest challenges of the upcoming decade. Indeed, the correct prescription of antibiotics is crucial for successful treatment and the WHO states that completing the full length of the treatment is just as important. But what is actually the correct length of treatment for all the different antibiotics and diseases? How many ward rounds on ICU's have I spent with microbiologists (the maybe most important specialists on our sides!) wondering on how they always had a straight answer on the correct length of treatment. 7 days, 10 days or sometimes 21 days... a little mystery to most intensivists, until now! Hitchhiking though the the wide space of the internet I finally found secret to this question. Back in the year 2010 Paul E. Sax, a Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School him self, posted an excellent blog for the NEJM Journal Watch website. Inspired by a New York Time article by Harvard Professor Daniel Gilbert he finally gave insight into one of the great mysteries of medicine: To figure out how long antibiotics need to be given, use the following rules:

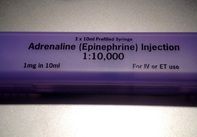

That did not occur by chance Wow, not much more I can add! Paul E. Sax, NEJM Journal Watch HIV/AIDS Clinical Care, October 22nd 2010 NYT article by Daniel Gilbert from October 2010  Guidelines on advanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation around the world, including the ACLS guidelines, are based on four important concepts: mechanical resuscitation (CPR), defibrillation, airway management and also application of vasoactive drugs. The application of these drugs is intended to improve hemodynamics and the heart's responsiveness to defibrillation. What some of us might not be aware of though, but has already been mentioned by the '2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations' and the 'European Resuscitation Council Guidelines' in 2010: There is actually no definitive evidence that the application of these drugs provides any long-term benefit for these patients. While vasopressors are intended to improve coronary and cerebral perfusion and therefore successful defibrillation and neurological outcome, there is actually some concern (animal and registry studies) that this might actually decrease microcirculation and cerebral blood flow as well as increase myocardial oxygen consumption and cause post-defibrillation ventricular arrhythmias. Also the use of anti-arrhythmic drugs as well as their combination with vasopressors lacks evidence of any impact on survival. Another interesting fact is that we have no idea about ideal dosage or optimal timing of these drugs... should they be given continuously? This and many more questions and facts are discussed in an interesting review article by Sunde and Olasveengen in Current Opinion in Critical Care. They conclude that there is no evidence to support any specific drugs during cardiac arrest and that healthcare systems should not prioritise implementation of unproven drugs before good quality of care can be documented. Are we heading towards an era of drug-free resuscitation? Sunde K et al. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014 April 16 Article accessible here |

Search

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed